The standing artillery of Atlanta

Most US cities have their house of cards. This is ours.

John is my next-door neighbor. We live north of Atlanta in a suburb carved out of the Southern Appalachian Piedmont Forest.

John would be high on a list of reasons I love living here. Once in a while I catch sight of him standing in his backyard, tall and handsome. And I think How lucky am I, living next to John.

At the same time, John scares the living shit out of me.

John is a 100-foot loblolly pine tree. He stands in his backyard, 60 feet southwest of our house, situated on a slight downslope toward us, right between us and the prevailing winds.

Nothing is more special and wonder-inducing about living here in the communities north of Atlanta than the embrace of this immense forest. Like other wonders in my life, I stop noticing the forest for months at a time. Then suddenly, there it is again. Wow.

Then a storm warning comes — and suddenly I see us surrounded by gargantuan storehouses of potential energy, several of them pointed at us like standing artillery.

Because Georgia's soil is a hard red clay, and John is a pine, I know that he has a dinner-plate root structure. Unable to penetrate the clay, those roots notoriously splay out sideways, shallow in the topsoil. I know this because of something Atlanta's trees not infrequently do: they fall over.

In the wooded park where my wife and I walk, we often see downed pines after a storm — tons of wood lying quiet on the ground. I imagine the incredible power and roar as wind and gravity pulled those tons to the earth.

If a tree came down whole, as they often do, we see at the lower end a dinner plate of roots up to 20 feet across, poking embarrassed into the air.

Our trees, ourselves

Atlanta is famous for its urban and suburban forest, with 45-48% coverage in the metro area — an estimate 110 million trees in all. They are woven into our identity. Every city and town has strict regulations to preserve that asset — not always strict enough, in our collective opinion. (As with all of the intersecting hypocrisies of modern life, most of us howl about preserving trees while living in clear-cut spaces ourselves.) In my particular city, a tree of more than a four-inch trunk diameter cut down without a permit draws a fine of $10,000, plus the cost of planting a replacement. Still, developers and loggers seem to have little trouble getting those permits, and a steady drumbeat of new developments claims hundreds of trees at a whack.

The Piedmont was historically an oak-hickory forest mixed with short-leaf pine. Centuries of logging and building altered that landscape. One result is the loblolly, a top-heavy pine that thrives in "disturbed" areas. Our neighborhood is just over 30 years old, and so is John, most likely. Loblollies grow fast, up to three feet a year. Which explains why I didn't notice John when we moved in 15 years ago: he'd have been closer to the height of other trees around here, maybe 40-50 feet tall — and still, crucially, 60 feet away from our bedroom.

I think it was during the pandemic, when we were all doing a lot of vacant staring, that I noticed we had slid within easy reach of our handsome neighbor.

There are 13 trees in our backyard, and about the same for each of our neighbors. Only four of those 40-ish trees present a serious risk to our house. Paul is also a loblolly, perhaps 80 feet tall. He's in our own yard, much closer than John. But between Paul and our house is George, an old-growth hickory. Hickories have a more balanced crown, much harder wood, and a strong, deep taproot system. Lennon and McCartney will go down before George. And before Paul could reach the house, he would fall into the sturdy arms of George, slowing him at least, maybe stopping him.

Between us and John, though, is open air.

Yoko and Linda are maples, capable of hitting us, but relatively small and sturdy. Ringo stands in the other neighbor's yard, easily 90 feet tall, also heavily inclined toward us, and also well within reach. But like George, Ringo is a hardwood of some kind, oak maybe. His mom, like us, is vigilant about what grows in her space. So like us, she almost certainly has an arborist come around once in a while to check things out.

I don't know if John's dad does that. I should ask.

Because when the wind blows, these trees dance. And when the wind blows hard, they thrash and roar. Deciduous trees are riskier once the leaves are in, creating a top-heavy canopy that acts as a sail. But the pines, those tippy pines, have needles all year round.

Our eventual reckoning

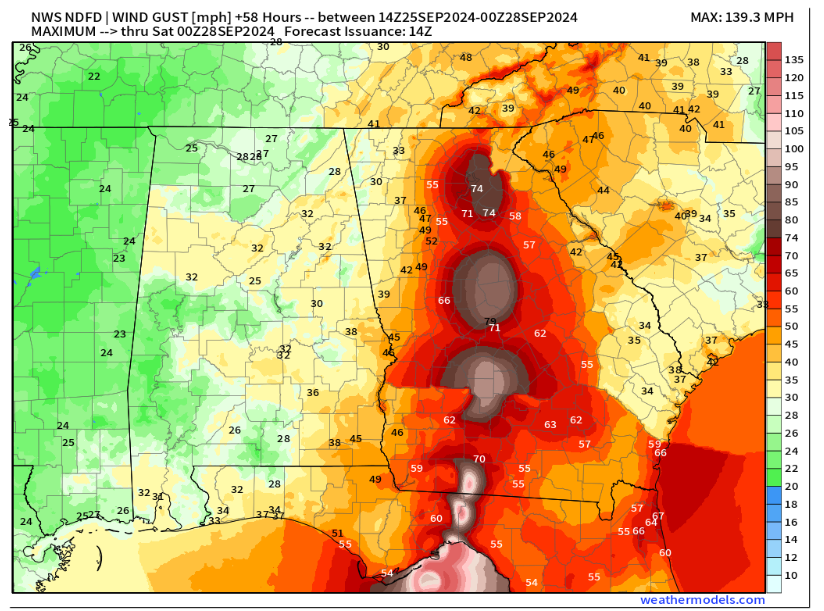

The storm this past Sunday morning spawned three tornadoes in Georgia and straight-line winds of 60-70 mph just about everywhere. Hundreds of trees came down in a single county 40 miles from here. Seven fell on one house. A man was killed sleeping in his Atlanta bedroom around 2 am as we slept in our Johnward bedroom, 30 miles to the north.

Meteorologists said if Helene had hit Atlanta directly as predicted last September, it had "the potential to be Atlanta's Hugo," a storm that devastated the Carolinas in 1989 and was the costliest US hurricane ever at the time. One article titled "Metro Atlanta is not made for storms like Helene" cited the trees specifically as the greatest threat to life and property.

But Helene did not meet the Fab Four. She banked slightly to the east this time, devastating North Carolina instead. We got our highest three-day rain total in 104 years but were spared the 100 mph winds and the predicted decimation of as many as 100,000 trees, with a guaranteed record loss of life.

As with most dodged bullets, we did a cartoon wipe of the brow, sent thoughts and prayers to North Carolina, and kicked the can down the road.

It's not just us. Most major cities in the United States are whistling past the graveyard in one way or another. The eventual earthquake we called "The Big One" when I lived in LA will claim that city. More and stronger tornadoes are coming for Dallas and Oklahoma City. For Miami, New Orleans, and Houston, it's hurricanes and rising sea levels, and fires throughout the West. Pretty much everybody has their house of cards.

For Atlanta, it's two billion tons of wood, standing in precarious columns around our homes.

If Helene had hit the city directly, it might have catalyzed a sudden reckoning between Atlantans and our environment. But like LA and The Big One, our storm is coming. From beloved asset to be preserved at all costs, the trees looming over us will suddenly transform to a feared threat. After the storm that wakes us up, I picture us raising our eyes to the weather map to see a line of storms in the gulf, triggering a massive citywide cull of our forest, punctuated by the storms themselves. It's hard to picture the result, the dropped horizon on all sides and exposure to the sky.

I'll miss John. More importantly, I hope he misses me.