Go easy on the weatherfolks. It's chaos out there

Weather forecasts are tangible, daily predictions of the future. But it's damn near impossible to get it right—and that's about to get much worse.

On April 30, 1865, the first weather forecaster, a man named FitzRoy, took his own life.

Although he wasn't the first to try to figure out if it would rain tomorrow, FitzRoy is considered the first to attempt it scientifically. Communications technology had finally made it possible for a forecast to travel from remote stations more quickly than the weather itself. He set up a network of observation stations through the UK—especially in the west, the direction of the prevailing winds—and in 1861 began issuing storm warnings that he called "forecasts," the first use of the term.

FitzRoy wasn't just a hobbyist but a vice admiral in the British Navy. His quest was not about planning summer picnics but saving lives. Sudden storms at sea took sailors and ships every year. The ability to know a storm front is coming would be an enormous contribution, something he knew well from his own years as a ship's captain.

A recent disaster had also underlined the need. In 1859, the Royal Charter sailing from Melbourne, Australia with 500 people was caught in a violent storm within sight of Anglesey on the British coast. The ship was flung onto the rocks with such force that only 50 people survived.

The disaster made a deep impression on Admiral FitzRoy, who was then the officer in charge of weather observations—an important distinction from forecasting future conditions.

If a British ship's captain in the 19th century named FitzRoy rings a bell, it should: This is Robert FitzRoy, captain of the HMS Beagle and cabin mate of Charles Darwin for the five-year voyage that by Darwin's own account gave rise to his theory of evolution by natural selection.

He is also the FitzRoy who, at the Huxley-Wilberforce debate of 1860, loudly denounced Darwin's Origin of Species and, according to one observer, "lifting an immense Bible first with both hands and afterwards with one hand over his head, solemnly implored the audience to believe God rather than man." FitzRoy later added that had he known Darwin's views, he would not have taken him aboard the Beagle. (A moot point, since Darwin's views were quite conventionally religious when he stepped aboard.)

One year later, FitzRoy was engaged in the marginally more productive work of predicting the future.

Lacking the modern instruments and global reach of today's forecasters, who still struggle mightily with accuracy, his storm warnings often missed the mark. A raging storm, finished lashing Cornwall and barreling toward London, dissipates inexplicably over Hampshire. A week later, clear skies in every direction suddenly spawn blooming thunderheads.

It was baffling to him.

The endeavor to foretell the weather involves the closest attention and perseverance, often without the hope of success, yet pursued with the earnest desire to save life and property—FitzRoy's journal

Repeated misses exposed FitzRoy to scathing ridicule. The owners of fishing fleets, whose crews often refused to sail without a favorable forecast from FitzRoy, were especially vocal. When one FitzRoy-forecasted storm after another failed to materialize, they demanded that Parliament shut down the new weather service.

But Fitzroy was less haunted by storms that failed to show up than by storms that materialized despite his predictions of clear skies and calm. Over time, several commercial and naval vessels that had headed to sea on what turned out to be the false promise of smooth sailing were taken unprepared by sudden squalls, losing lives, ships, and cargo.

"The responsibility weighing upon the mind of a man who ventures to predict the violence and direction of storms, to an extent which may affect the lives of hundreds of his fellow creatures, is sufficient to tax the utmost powers of a mortal," wrote FitzRoy in his journal. "It is the anxious fear of making mistakes, of giving false security, or causing needless alarm, that weighs heavily upon me."

In April 1865, the hail of criticism, the idea that he was actually increasing risks to sailors, his deepening financial troubles, and a longstanding tendency toward depression, combined to lift a razor to his throat.

My heart is full of fears, and my mind often strays to the consequences of my forecasts, knowing the trust that people place in them and the potential for grave error—FitzRoy's journal

By year's end, the Board of Trade had shuttered his Meteorological Department.

One fact about FitzRoy's early efforts should get a bitter nod from today's weather forecasters: Modern analysis has shown that his forecasts were right 70 percent of the time. But then as now, negativity bias leads us to ignore the hits and record the misses.

Why weather forecasting is so insanely difficult

The best way to grasp the impossibility of predicting the weather in any given place and time, much less every place and time, is to understand chaos theory.

Chaos theory is about the sensitivity of complex systems to initial conditions. In any complex system—traffic, for example, or financial markets, or ecosystems—a tiny difference in one initial condition can result in a massive change in outcome. So any degree of uncertainty regarding that initial condition yields an enormous number of possible outcomes.

Now add the fact that a dynamic system like weather doesn't really offer "initial conditions." Everything is in flux all the time, continuing in motion from previous conditions.

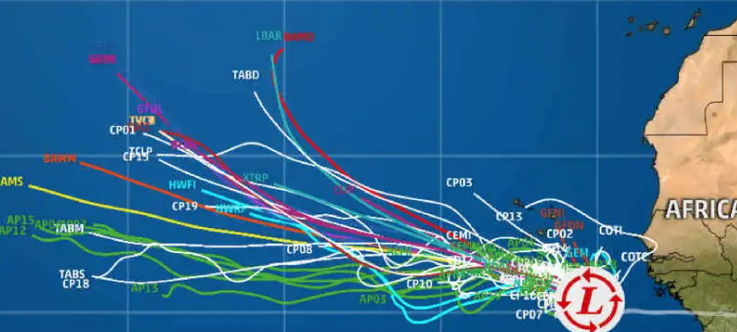

Hurricane spaghetti models offer a perfect visual capture of chaos theory. They basically answer the question "Where will the hurricane go?" with "That depends."

Some weather phenomena are easier to predict than others. Years ago, during an interview on NPR, the chief of forecast operations for the National Weather Service made a statement I've never forgotten: "I can confidently tell you within a degree or two what the temperature will be in your backyard a week from now," he said, "but I can be wrong about precipitation this afternoon."

This examination of the chaotic science of weather forecasting continues in Part 2 with a look at how climate change will make a tough job nearly impossible—just when we need it most.