You think weather forecasting is bad now? Welcome to 2070

It's not just the size of the storms that future generations will deal with. It's the terrifying unpredictability.

Part 1: Go easy on the weatherfolks. It's chaos out there

The year is 2070. As climate has changed and storms have become more catastrophic, it's more important than ever to have accurate forecasts. But as weather intensity grew, so did uncertainty. The difference between a calm, sunny day and a calamity with a high casualty count is often a coin toss.

Weather forecasting, a deeply difficult undertaking in the early 21st century, is now just about impossible.

Part 1 explored how the chaos of the atmosphere makes it hard to know (for example) where and when a violent storm will spawn and the exact direction it will take, which in turn makes it difficult to predict how that will affect other conditions, and so on. But that inherent chaos is about to get significantly worse.

By massively increasing not just temperatures but wind speeds, number of major storms, adjacent high-contrast conditions, and dozens more variables, climate change within our children's lifetime will make our weather today look as predictable as the electric slide.

Why the climate crisis will confound weather forecasting

Over the remainder of this century and beyond, the climate crisis will lead to more extreme and unpredictable weather events and greater variability, making it harder to forecast accurately. But just as bad will be the scrambling of the reliable patterns that have made weather forecasting at all possible.

We rely heavily on the stability of the jet streams. As a 2022 paper in the Journal of Climate puts it, "Weather prediction depends critically on the dynamics of the westerly winds that dominate the large-scale atmospheric circulation." When those jet streams significantly meander, it kneecaps our ability to predict what's coming. In 2010, a sudden shift in the subtropical jet stream attributed to the climate crisis poured heated air from the Sahara into Russia, killing more than 55,000 people. A similar shift in 2019 shattered temperature records across Europe, including an all-time high of 108.7F in Paris, killing 4,000 people across the continent. And a stalled jet stream in the winter of 2013-14 caused catastrophic flooding in the UK.

Because they involved breaking long-established patterns, all three catastrophes caught weather forecasters largely by surprise.

Reliable ocean currents are so vital to global weather systems that the oceans are often referred to as an extension of the atmosphere. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a system of currents that regulates the transfer of heat between the equator and the poles by bringing warm water north and cold water south, is slowing down as the melting of the Greenland ice sheet pours cold water into it.

Though the complete collapse of the AMOC is not as imminent as breathless media would have us believe, the slowing of the system has already shown strong effects, including colder winters in Europe, higher temps in the tropics, and a greater difficulty in predicting hurricane paths. The eventual collapse of the AMOC is considered a tipping point in the global climate system. But long before it tips, it is confounding our ability to rely on long-established weather patterns.

Weather models start from an assumption of relative normalcy. Then every extreme event—every 500-year hurricane, every 1000-year flood—throws a wrench into predictions. As much as anything, the art of forecasting involves dealing with those departures from the norm.

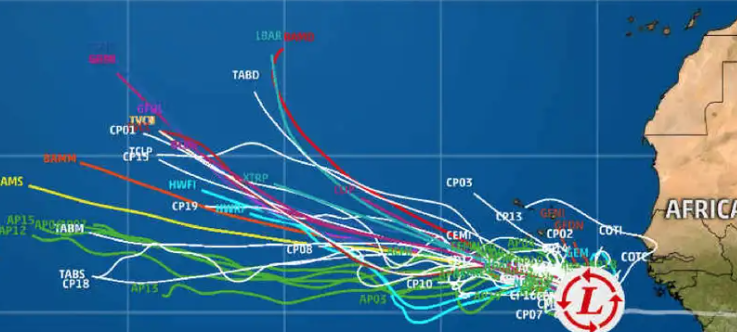

The many possible paths of a hurricane already yield something called a spaghetti model:

Double the number of storms and their average intensity and you end up with an Atlantic Ocean choked with overlapping piles of probabilistic pasta. Not only each of those storms but a thousand local weather events around the globe would be affected by this uncertainty in ways that simply couldn't be calculated. It's not hard to imagine that "depending on" will become the most common words in every weather forecast.

To anyone paying attention, it's already widely understood that our broken climate will yield more powerful storms. But the added dimension of living with extreme uncertainty about whether or when one of those storms will open over your head is too rarely discussed.