What David Brooks's search for God can teach secularists to embrace and avoid

Brooks's essay is the kind that often exasperates nonbelievers. But is there something of value to secular civilization in his God-optional conclusions?

There will never be a secular civilization until we secularists can produce the kind of essay New York Times columnist David Brooks just published about his search for God. The importance of the essay lies not in the content of his journey but in its seriousness and depth. Brooks confronts secularists with the old Kantian question—what can we hope for in life?

It is a sprawling essay—4,000 words in a newspaper!—and thus hard to summarize. But Brooks does describe his search in several lessons he has learned. These are worth attending to.

When the search is the point

First, Brooks asserts that the search for God is not, as he had thought, a matter of belief—not about arguments over whether God exists. The search for God is more akin to falling in love. The experiences that lead one to God are “numinous”—"the scattered moments of awe and wonder that wash over most of us unexpectedly from time to time.”

The second lesson is that religion is not made up of such moments. Quoting the poet Christian Wiman, Brooks writes that “Religion is the means of making these moments part of your life rather than merely radical intrusions so foreign and perhaps even fearsome that you can’t even acknowledge their existence afterward.” Religion creates a framework for spirituality as the road to God.

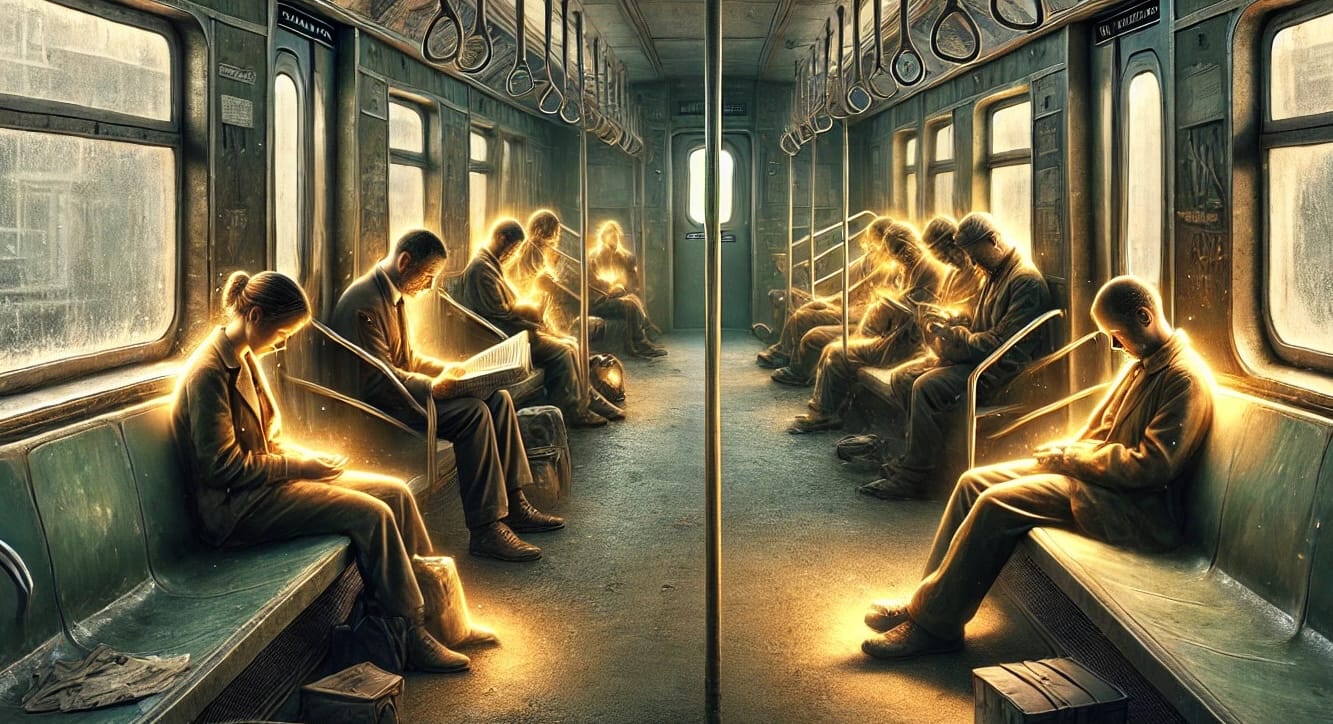

Brooks’ third point is that spiritual experiences can and should change the believer’s consciousness and conduct. These experiences have an ethical component. For Brooks, the sudden realization of his shared humanity with others on a crowded subway car led to his contemplation of the “infinite value” of each person.

Brooks refers to this value as the “soul” of each person and it leads him not only to wonder about a “soul-giver” but also about “a spiritual element to the universe as a whole.”

This third point about morality deepens in the essay. Brooks confronts in traditional prayer what has been called the upside-down world of the Bible—the last shall be first/the meek shall inherit the Earth. Brooks feels he has glimpsed “a goodness more radical than anything I had ever imagined, a moral grandeur far vaster and truer than anything that could have emerged from our prosaic world.” Brooks is “morally elevated,” “seized by joy —by the sensation that I had just been overwhelmed by a set of values of intoxicating spiritual beauty.” This convinces Brooks that we “are embraced by a moral order.” Cruelty does not just seem to be wrong as a matter of opinion, but violates this universal moral order.

This change in consciousness makes a demand on Brooks. He feels “pulled by a goodness that seems grand and far-off.” Brooks quotes the historian George Marsden about Martin Luther King, Jr.: “What gave such widely compelling force to King’s leadership and oratory was his bedrock conviction that moral law was built into the universe.” Brooks is inspired by “the example of those who serve the marginalized with postures of self-emptying love.” He is led to personal sanctification—“the desire to become a better version of myself”—and Tikkun Olam—“the movement to heal the world.”

The overall effect of these experiences on Brooks is to quicken his life—he refers to this as being “remusicked.” He now lives a “grand adventure” “in an enchanted world.” His great yearning, never to be satisfied, is “to experience greater and greater intimacy with God.”

All of this is interrelated. This is the promise of the ancient religions and wisdom traditions that goodness, truth and beauty are one. This is the wisdom of the Jewish prayer, the Sh’ma, that God is one.

What does this have to do with nonbelievers?

What does Brooks’s search for God teach us nonbelievers? What questions does it raise?

Brooks is not alone. The media is filled these days with reports of a renewed interest in religion, from fellow New York Times columnist Ross Douthat to a long report in The Free Press by Peter Savodnik. It seems that many people today are finding Max Weber’s disenchanted world of science and reason unfulfilling.

But this unhappiness follows not from the decline of religion, but the failure of secularism to offer anything more than a tired, dispirited and unconvincing materialism in place of religion—a failure to offer a Hallowed Secularism, as I put it in the title of a book years ago. This renewed search for religion is not really about religion as such. It is a search for a universe that is on our side, as the theologian Bernard Lonergan put it—a universe of purpose, goodness and beauty.

That this is not really the search for religion’s God becomes clear as Brooks carefully skates around any of the actual content of the Jewish and Christian traditions in which he is dabbling. Brooks is part of the distinction Savodnik makes between theological Christianity and cultural Christianity. Brooks does not want to confront God as the Lord of creation. This leads Brooks to ask really silly questions he cannot possibly take seriously, like “Why did God ask Abraham to murder his son Issac?” Nothing in Brooks’s spiritual experiences suggests that anyone receives a Western Union telegram from a God telling that person what to do. Brooks’s attempted movement from Paul Tillich’s “awareness of the infinite” to the dogmas of the actual religious traditions is a failure.

Clearly, a life enmeshed with awe and wonder is available to the secularist. There is already a well-established phrase for this search—many secularists say they are “spiritual but not religious.” Even a secularist as committed to sober reason as Richard Dawkins wrote a book in 2011 entitled The Magic of Reality. Many of the great scientists and mathematicians in the West have been intoxicated by the beauty of truth.

Unfortunately, most of us are not scientists or mathematicians and cannot access this plane of beauty. For us, as Brooks points out, spiritual experiences tend to be scattered and not really meaningful in terms of our consciousnesses or conduct. Brooks refers to this as “vague spirituality.” Religion, he asserts, in contrast, creates a story in which these experiences make sense and teach lessons.

If we secularists value transcendence, if we believe that secular life also can be a grand adventure—beautiful and exciting—even for ordinary people, we need an accessible story of reality that similarly creates a framework for meaning.

A lot of work along this line is going on, from Brian Swimme’s The Universe Story, to Bobby Azarian’s The Romance of Reality, to Nicholas Christakis’s Blueprint. These are fully natural antidotes to reductionist materialism. We must simply put as much effort into constructing a fulfilling story of existence as we now put into the needed political and legal efforts we make to defend secularism from religious overreach.

In addition to a story, there will have to be attention to spiritual practices. Brooks’s quickened life does not just happen. It takes effort and discipline. Secularism needs institutions of community and purpose for encouragement and sustainability. I have no idea what these institutions and practices will look like. But they are necessary.

There is a political aspect to this as well. Brooks is right that Martin Luther King, Jr.’s power and authority arose from his certainty that the arc of the moral universe is long, but bends toward justice. Racism was false and therefore eventually would fail. Racists themselves would come to see that truth. And this, for all our failures and inadequacies, has happened to a great extent compared to the world of King’s time.

That is not an isolated experience. Human history, and natural life as a whole, support King’s view. Faith in truth and justice moves political disagreement from mere struggle for power to potentially redemptive.

To put this simply and plainly, MAGA is doomed to defeat because its cruelty and incoherence are false. Undoubtedly, it will do a great deal of damage in the meantime. But we don’t actually have to worry that this is the future. That doesn’t excuse us from the political work of opposition but it should help us see our political opponents as misguided rather than evil. Our work in opposition ultimately helps them, too.

Of course, that also means that not everything that Trump does will be bad. We have to be open to our own failures that Trump was elected to address.

What remains when the personal God is abandoned

Is there any way to link our secular path and Brooks’s religious one? The answer is most certainly yes. Brooks goes wrong in thinking he is looking for a kind of person who is God and therefore behaves like a person. That error is the source of the simplistic notion of the wonder-working God. Many theologians have argued that Brooks’s search for this kind of God is a form of idolatry.

But if that understanding of the personal God is abandoned, there is a lot, almost all, of Brooks’s essay that a secularist can accept and learn from. The issue concerns fundamental ontology—what is real. If the universe really is a kind of mysterious goodness, and we receive intimations of that goodness in spiritual experiences, that is a great story. It is a natural story and a reasoned story. It does not require any surrender of scientific discovery. It is in fact good news. It can be our secular gospel.