The emptying of Florida

Many Floridians currently fleeing Hurricane Milton are unlikely to return. It may be the first big step in the predicted near-emptying of the climate-exposed peninsula.

Mass migration has long been one of the predicted consequences of climate change. But Americans tend to picture vague displaced hoards in faraway places.

Florida is about to bring that image home.

As I write this, the monstrous Hurricane Milton is closing in on central Florida. It's the second catastrophic storm to hit the coast in three weeks, and every northbound highway is choked with cars packed with people, pets, and belongings.

Most are planning to return. But if the storm packs the expected punch, there's a chance that many will have nothing to return to, and a hurried evacuation will become a permanent move.

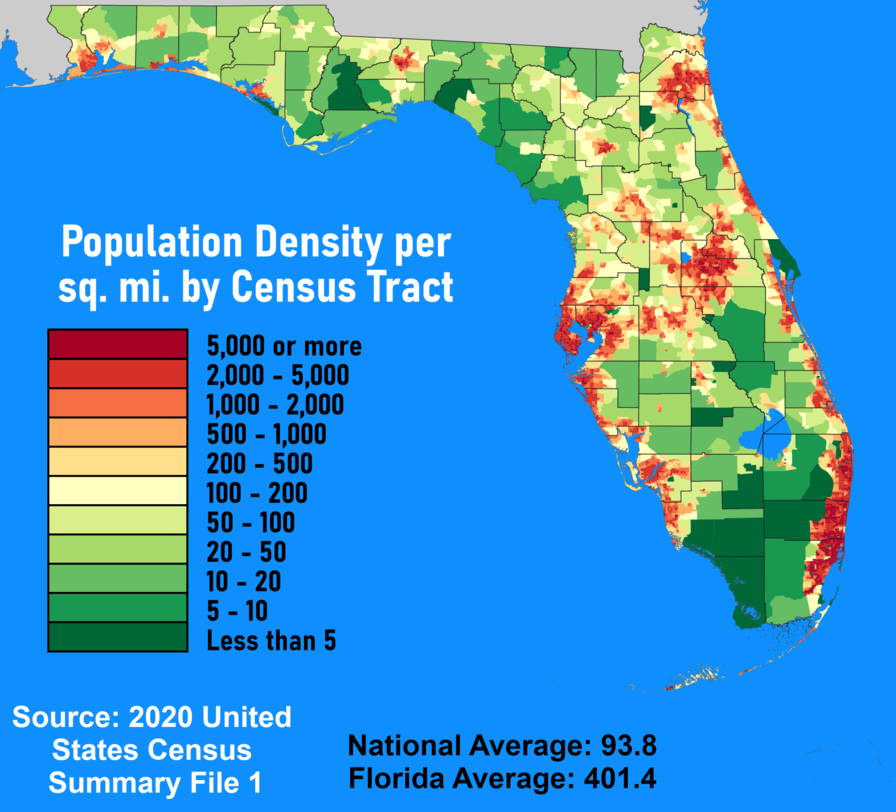

The Florida peninsula is wrapped on three sides with warm water, a big part of its long-term draw. That means it's also wrapped in its own population, densely clinging to the lovely shores:

As rising seas, stronger hurricanes, and increased flooding become the new normal, a significant percentage of the state’s population may soon have no choice but to leave permanently. This would reshape not only Florida but the regions where displaced Floridians are likely to resettle, including my current home of Atlanta.

But the ability to escape will be uneven, leaving behind those least equipped to face the endless storm.

A never-ending train of disasters

Florida has always been vulnerable to hurricanes, but the greater frequency and severity of these storms have made many areas nearly uninhabitable and uninsurable.

Florida has the lowest high point in the US (Britton Hill at 345 feet). That pancake geography and 8,436 miles of coastline mean that even small rises in sea levels will result in devastating floods.

But according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), it isn't small rises we're talking about. Sea levels around Florida have already risen by about 8 inches since 1950 and are expected to rise another 2 to 6 feet by 2100, displacing up to 6 million Floridians.

Dr. Jesse Keenan, a climate adaptation expert at Tulane University, has been vocal about the potential for a mass migration out of Florida due to these growing threats. And it's not just about the destructive storms, he says, but our collapsing ability to respond.

Up to now, he told ProPublica, we have essentially "socialized" the consequences of development in high-risk areas. But as mitigation costs rise, and insurers pull out, and bankers divest, people will increasingly shoulder the risk and expense on their own. That, he says, is when the real migration might begin.

Milton may speed up that timeline.

The rest of the world

The prospect of displaced Americans is getting our attention. But populations in low-lying countries like Bangladesh and the Maldives are already being displaced. In 2020, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre reported that climate disasters had already displaced more than 30 million people worldwide.

The World Bank has projected that by 2050, up to 216 million people could be forced to relocate due to climate change, with sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America bearing the brunt of these displacements. And while Floridians (or Californians fleeing wildfires, or Arizonans fleeing weeks on end of 110+ degree heat, etc) may find it easier to move within the United States, those in poorer countries are often left with fewer options and forced to live in increasingly precarious situations.

Left behind in Florida

While millions of Floridians are expected to eventually leave the state for good, the option isn't open to everyone. As climate disasters intensify, those with financial means will be better able to rebuild their lives elsewhere. But low-income residents and those in marginalized communities will more often be forced to stay and face the storms with dwindling means to protect themselves.

Keenan points to Black and Latino communities as those most likely to be stranded in an increasingly-unlivable state. Even those who own homes, often their primary asset, will find it increasingly difficult to sell as property values collapse in flood-prone areas.

Compassionate assistance to those left behind will be crucial, and no doubt hotly debated.

What's the plan here?

There's a lot of belated talk about how best to deal with the catastrophe. Florida will need continual mitigation, like seawalls, flood defenses, and improved drainage systems, for as long as people live there. But experts have noted that this only delays the inevitable. At some point, we will be looking at humanitarian relocations of the type and on the scale of operations in Rwanda in 1994, Darfur in 2003, and Syria in 2011.

States expected to receive climate migrants will also need help to prepare for pressures on housing, schools, and healthcare systems. And Florida will need to grapple with the socioeconomic consequences of losing a significant portion of its population (and the more affluent portion at that).

And that's just Florida.