Why degrowth is (still) wrong

Reading Time: 6 minutes Earlier this month, I wrote an essay against degrowth, the position that drastic reductions to the modern lifestyle are our only hope of saving the planet. I argued that, to the contrary, renewable energy promises a future of greater abundance even as we tread more lightly on

A while back, I wrote an essay against degrowth, the position that drastic reductions to the modern lifestyle are our only hope of saving the planet. I argued that, to the contrary, renewable energy promises a future of greater abundance even as we tread more lightly on the Earth. It’s the very rare case where we can have our cake and eat it too.

Pro-degrowth economist Timothée Parrique wrote a reply, “A response to Adam Lee: Is degrowth wrong?” I’d like to address his major points.

Framing the problem

What’s ironic is that, if you put our ideal worlds side by side, they wouldn’t actually differ all that much. I’m confident Parrique and I would agree on many of the changes that the planet needs.

For instance, I think it’s good that we’re becoming an urban species. Cities are engines of opportunity, making it easier for people with needs and people with skills to find each other, creating jobs and wealth. Because of their superior density, they take up less land and make services and infrastructure more efficient. The multiculturalism of cities also makes people more open-minded and socially progressive.

It’s better to design neighborhoods at human scale, centering pedestrians and expanding mass transit, rather than designing them around automobiles. Cars are resource-intensive beasts, gobbling up space that could be used to house humans, and car commuting is a life- and health-destroying ordeal that produces wasteful sprawl.

It’s better if people eat locally and seasonally and choose a mostly plant-based diet. Meat and long-distance imported crops should be luxuries for special occasions. Unsustainable monoculture farms and CAFOs should be abolished in favor of regenerative agriculture.

As I said previously, the mentality of ever-greater consumption is wrong-headed. Beyond a certain point, more material goods don’t produce happiness, and may even detract from it. A simpler life with more leisure and and more community is a better life.

Where we begin to diverge is this: I don’t believe humanity has to reduce our economic capacity. Instead, we should redirect it into areas that make a better world for everyone. This is a both/and situation. Right now, most of our productive power is squandered on the treadmill of consumerism, on mutually destructive zero-sum competition, or on rent-seeking that enriches the few at the expense of the many. We can change this.

In this possible future, what I call Industrial Revolution 2.0, ultra-cheap energy will put an end to resource conflicts. Combined with AI, robotics and other advanced technology, it will also eliminate the need for human labor to do the drudge work of civilization. With a secure baseline of material comfort, we’ll all enjoy lives of greater happiness and abundance, with more leisure, more time for scientific research and the arts, and more freedom for other pursuits that really matter. (Those who’ve read my novel Commonwealth may recognize this as essentially a description of the Pacific Republic.)

Where’s the barrier to decoupling?

The biggest point where we differ is the feasibility of “decoupling”—that is, replacing our current power sources with green energy so that technological progress can continue without wrecking the planet.

Parrique says that observed rates of decoupling aren’t fast enough to save the world from climate disaster. That may well be true. However, this argument is like the North Carolina legislature saying that observed rates of sea-level rise don’t threaten coastal development, so there’s nothing to worry about—and never mind what those know-it-all scientists are predicting.

In both cases, the fallacy is the same. There are good reasons to expect that a naive extrapolation of the present into the future will fail.

Just as climate scientists expect the rate of sea-level rise to accelerate, there are equally powerful trends in the opposite direction. The price per watt of energy from solar and wind is dropping exponentially. It’s literally decades ahead of the International Energy Agency’s price forecasts. For the same reason, the amount of installed renewable capacity has blown past expert predictions.

Given facts like this, I have to ask skeptics what, specifically, they think the barrier to decoupling is. There’s a statistic I’ve often quoted: the Sun delivers more energy to the Earth in an hour than humanity uses in a year. Clearly, there’s more than enough clean power available to supply our needs. Costs of solar panels, batteries and other components are already competitive and still dropping.

The only major problem, it would seem, is whether we have the political will to make the green transition happen soon enough. I grant that this is a formidable issue; inertia is a difficult force to overcome. However, this leads to a patently obvious follow-up question…

How fast can degrowth happen?

Parrique says that decoupling won’t arrive in time to save us. He might be right about that; no one knows what the future holds. But there’s an obvious rejoinder: How fast can degrowth happen?

After all, what he’s proposing is a sweeping overhaul to almost every aspect of the Western lifestyle. Regardless of their long-term desirability, many of these changes would require sacrifices and the loss of conveniences that millions of people are used to.

Degrowth would affect how and where we live. Most suburbs and exurbs would have to be either abandoned or radically reimagined. Millions of people might have to migrate into cities, trading large private houses for small apartments.

Degrowth would affect what we’re able to buy. There’d be no more shopping malls, no more e-commerce companies delivering the world to your front door, and no more supermarkets offering a grand diversity of food. You’d own and eat only what could be made or grown within, say, a hundred miles.

Degrowth would affect how we work. Many industries would collapse, while others would be radically transformed. Tens of millions of people would have to learn new skills.

Some of these changes might be beneficial in the long run, but that’s not the point. The point is: How quickly can we expect people to go along with such a radical upheaval? Is it reasonable to believe that this can all happen faster than replacing coal power plants and gas pipelines with solar farms, wind turbines and battery storage? Which of these is the greater task?

When I asked Parrique about this on Twitter, he offered a handwaving reply about how COVID-19 showed that major change can happen quickly:

This may be technically true, but most of the pandemic adaptations, like universal mask-wearing and travel bans, (1) were always understood to be temporary; (2) were motivated by a salient and imminent threat; and (3) even at that, were resisted ferociously and at times violently by a sizable percentage of people. In Europe and Australia, there were riots. In America, a militia group allegedly plotted to kidnap and kill a governor.

Parrique’s degrowth prescription would entail far bigger changes. What’s more, we’d be doing it in response to global warming, which has always been greeted with even more apathy, denialism and politically-based hostility than the pandemic. Can anyone say with a straight face that this is realistic?

ON THE OTHER HAND | Curated contrary opinions

ML Clark, What degrowth is, and why it matters

Like it or not, the political consensus for this kind of drastic action doesn’t exist right now. I passionately wish it were otherwise, but wishing doesn’t make it so. On the other hand, in the U.S., a strong bipartisan majority supports renewable energy. It’s a change that’s already happening, and we can push it along.

Meanwhile, Parrique seems to have no plan, only a hazy hope that millions of people will somehow come around in time. This is as unrealistic as any other ideology which posits that the world will be perfect once its evangelists convert everyone.

Where’s the decoupling? Right here.

If decoupling is possible, it’s fair to ask what evidence exists for it. Here it is:

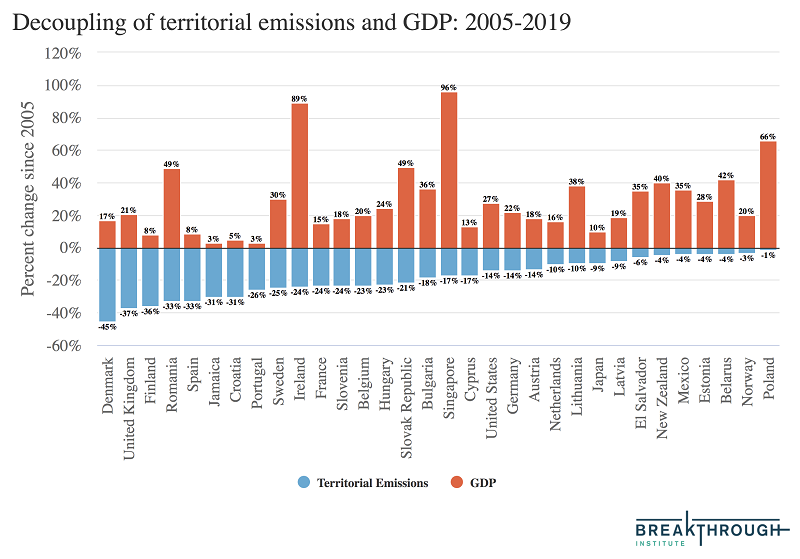

32 countries, including the U.S., have achieved economic growth together with an absolute drop in CO2 emissions since 2005. And yes, this holds when you include “consumption emissions”—meaning, when you count the carbon footprint of all goods consumed within a country, so as not to be fooled by the offshoring of industry.

In another article, Parrique complains that this isn’t good enough:

True, there have been a few cuts worth learning from here and there, but nothing near the magnitude, consistency, and durability of the reduction one would need to make the pursuit of economic growth ecologically sustainable. The more we study these decoupling unicorns, the more we should realise that they are the exception rather than the rule.

source

I think this betrays a basic confusion about what these graphs are intended to demonstrate. This isn’t meant to be conclusive proof that decoupling is already arriving and is going to save us all, so we can stop worrying. Rather, it’s what engineers would call a proof of concept: a demonstration that the thing we want to do is possible.

There’s no law of nature that requires that economic growth is always accompanied by rising carbon emissions. We haven’t slammed into any fundamental physical limit on what we can produce. We’ve hit limits on the way we currently do things… but that’s like medieval blacksmiths saying it’s impossible to make more horseshoes because there aren’t any more trees they can chop down for charcoal to fire their hand-run forges. It’s true that inefficient means impose limits on what we can do, but there are better alternatives available.

Of course, green energy isn’t the only thing we need to build a sustainable civilization. Deforestation, species extinction, depletion of topsoil and fresh water: these are all problems we should be concerned about. The challenge is immense in scale. But we shouldn’t let that immensity frighten us away from doing what we can do. Nor should we give up and declare that the problem can only be solved if human nature changes overnight.