MAGA and the questionable judgment of history

Even on the rosy assumption that this era ends, we will never see the return to relative consensus that was once possible.

There is a dream, now resident in many blue heads, of a time in the future when the current insanity is fading in the rear view. The verdict of history is in. Donald Trump and his populist movement are recognized by an overwhelming supermajority of Americans as a cancer and a cautionary tale. It has happened to other toxic political figures and cultural moments, like Nixon and Watergate, brought into clear focus by the passage of time.

That isn't going to happen this time, at least not in the same way.

The dream has less to do with Trump himself than with those around us—the fathers and sisters and friends and neighbors body-snatched by this virus, people we thought we knew. We want to hear them say they were wrong, that they don't know why they didn't see it before, but they're back.

When a few of these are amplified in the media:

...accompanied by comments about face-eating leopards, you could be forgiven for thinking you've had a taste of our future.

Probably not.

Actual regret may be fairly common, maybe even increasingly so. But the out loud reversal — abashed former MAGAs, eye-scales scattered on the ground, fessing to the error of their ways — that is a future scenario we should not generally expect to see.

We know this because of what MAGA is: a group with intense devotion to a leader or ideology, marked by manipulative practices, us-vs.-them mentalities, and resistance to contradictory information.

In other words, it's a cult.

Cults have been studied at length. One of the many things we know about them is that members generally don't announce their departures when they leave. Sometimes, sure. But more often, they quiet quit — gradually stop attending meetings, wearing signs of membership, defending the cult to others, and engaging in the practices that defined their connection to it.

But aside from a few outliers, they don't often make a proclamation.

Why would they? The shame of looking back to see what you were part of, not to mention all that badgering from friends and family who turned out to be right — who wants to confront that? There's also retaliation and shunning to avoid from those who remain inside.

Social identity theory notes that individuals derive part of their self-concept from the groups they are part of. Very strong identification with a group can lead to favoring in-group members and discriminating against out-group members. In political contexts, this can result in polarization, where individuals adopt the norms and values of their political group, leading to deep divisions and resistance to opposing viewpoints. This generates a deep revulsion to the idea of leaving, what psychologist and deprogrammer Steven Hassan calls "phobia indoctrination." Months or years spent defining yourself as a member of the group and learning to revile and pity those on the outside makes it painful to exit. Those who manage it tend to do so quietly.

The very different case of Nixon

Although the crimes of Richard Nixon have been rendered adorable in retrospect, he was deeply disgraced in the years immediately following his resignation, the ultimate example of corruption and dishonesty in American politics.

I know.

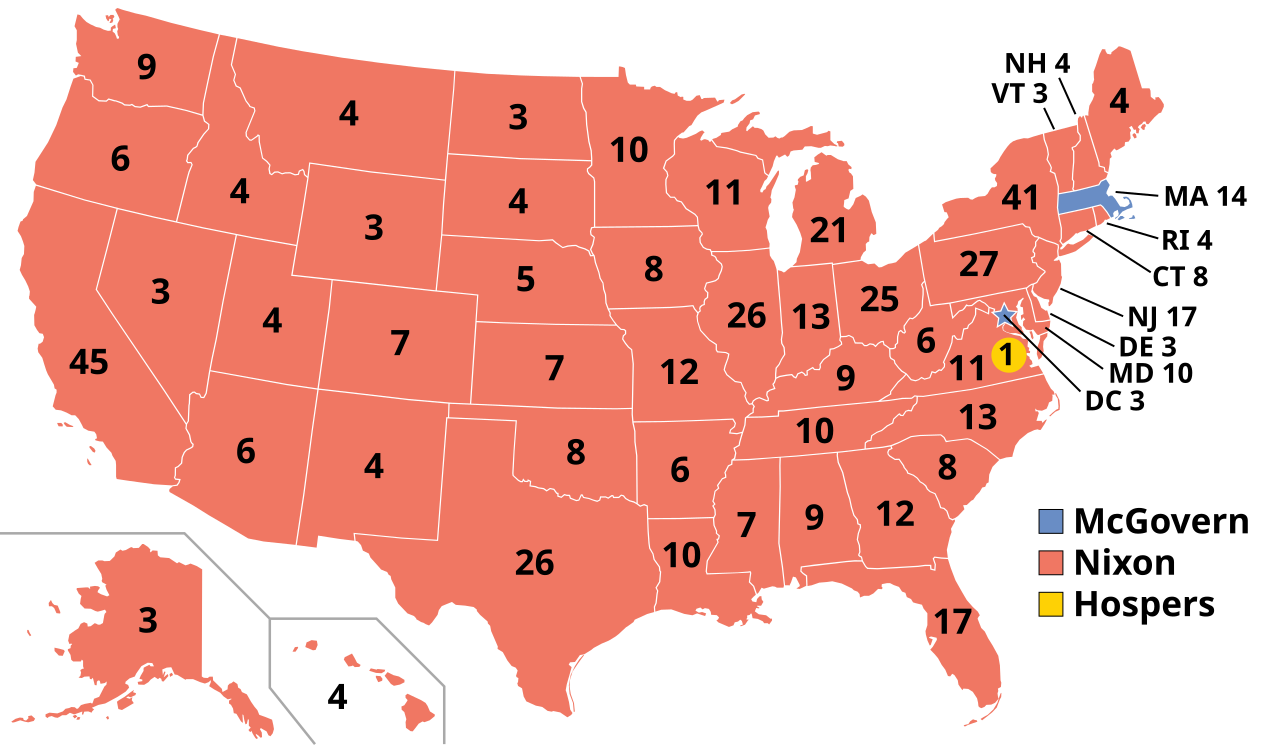

But it's worth remembering that before all that, Richard Nixon had a lot of full-throated supporters. He ran for re-election in 1972 on a platform of reining in the excesses and disorder of the 1960s. He won an astonishing 60.7% of the popular vote and 520 electoral votes, carrying 49 of the 50 states. Democratic nominee George McGovern received 37.5% of the popular vote and 17 electoral votes, winning only Massachusetts and DC. Nixon's margin of nearly 18 million votes remains one of the largest in US presidential election history.

His approval as he took the oath of office in January 1973 was 67%. By the time he resigned in August 1974, it had dropped to 24%.

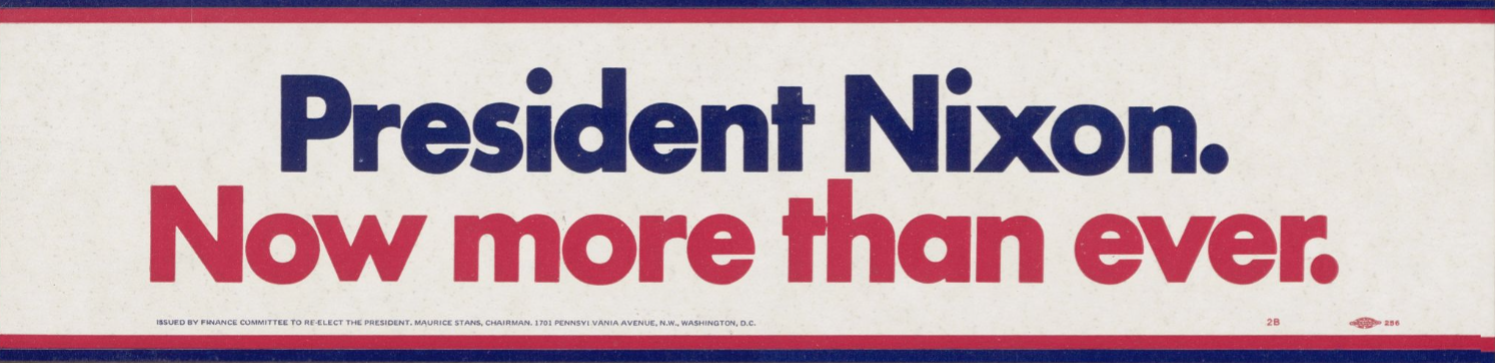

Did the 43% of Americans who changed their minds about Nixon during the 20 months of his second term do so out loud? Mostly not. Although his support was never at the cultish level of MAGA, what signs there were — bumper stickers, buttons, signs and T-shirts — quietly disappeared.

A million dads who had championed Nixon's law and order were suddenly sticklers for avoiding politics at the dinner table. All of those full-throated supporters had to figure out how to reconcile that part of their identities going forward.

Yes, there has been some redemption of Nixon, for his competence if not his ethics, and some whose whole personality is built around shocking the normals got themselves a photorealistic back tattoo of the disgraced leader. But after that leader's disorienting shift into the cellar, those who were not walking Batman villains had to find themselves again. Rather than a general announcement, they tended to avoid the topic, or reframed their support as conditional or misunderstood, or made false equivalencies. And then the return to silence.

But calling this a precedent for our current situation assumes something not in evidence — that Trump and MAGA will ever experience the kind of consensus condemnation that Nixon did.

Three major factors—fragmentation of media, political polarization, and the collapse of a shared historical narrative—make it nearly impossible for a single interpretation of Trump’s legacy to prevail across the American public.

Media

In Nixon’s era, most Americans got their news from one of three broadcast networks—CBS, NBC, and ABC—and a handful of national newspapers. These outlets generally operated under shared professional norms and similar standards of evidence. Walter Cronkite’s nightly broadcast, for example, reached nearly a third of American households and held tremendous authority. When these outlets uniformly reported the Watergate revelations, and when editorial pages across the country called for Nixon’s resignation, a collective narrative coalesced: Nixon had betrayed the presidency, and he had to go.

Today, the media ecosystem is radically decentralized. Americans now choose from an array of partisan outlets, social media platforms, podcasts, influencers, and alternative news sources. Each offers a different version of reality, often catering to ideological confirmation rather than consensus. For many of Trump’s supporters, Fox News is now too moderate; they turn to sources like Newsmax or Truth Social. Legacy media like The New York Times or CNN are dismissed by much of the right as illegitimate. There is no Walter Cronkite figure with the trust—or reach—to authoritatively close the case on Trump.

Politics

By the time Nixon resigned, many Republicans had turned on him. Senator Barry Goldwater and other GOP leaders made clear that Nixon no longer had the support of his own party, enabling a bipartisan moral judgment. But in the post-1990s political environment, partisan loyalty has hardened into identity. To a significant portion of the electorate, Trump is not just a candidate; he is a symbol of resistance to an establishment they believe has long betrayed them. Condemning Trump, therefore, is not just about facts—it is seen as a personal attack on those who support him.

This tribal dynamic means that even if new and damning evidence were confirmed by every traditionally authentic means, it would not carry the same force. Every accusation becomes a loyalty test, every judgment a political act. Trump has successfully framed every investigation — from impeachment to criminal indictment — as a persecution narrative. Nixon, by contrast, was abandoned by his party when the evidence became overwhelming. Trump thrives on the polarization that would have doomed Nixon.

The questionable judgment of history

Finally, there is no longer a central authority to write “history” in the way that post-Watergate America could. The dominant narrative that emerged after Nixon’s resignation — that he had rightly been held accountable by the institutions of democracy — was reinforced through school textbooks, documentaries, and political discourse for decades. It became a settled historical lesson.

But historical consensus depends on institutional trust and shared facts. In an era where universities, journalists, and historians are dismissed as ideologically compromised by wide swaths of the population, no such consensus is possible. Trump’s presidency — and post-presidency — will be remembered in fundamentally different ways depending on which epistemic community one belongs to. For some, he is a would-be authoritarian who attacked democratic norms and tried to overturn an election. For others, he is a persecuted outsider fighting a corrupt system. These two narratives are mutually exclusive and yet coexisting.

Because there is no longer a unified media, bipartisan political framework, or shared historical lens through which Americans view their leaders, Donald Trump will never face the kind of national consensus condemnation that followed Nixon. History now fractures on impact. Judgment is not rendered by a common culture but split along ideological lines that no longer speak the same language. Nixon’s disgrace was collective. Trump’s legacy will perpetually exist, like Schrödinger's cat, in two simultaneous, irreconcilable states.

The true believers of MAGA may retreat even further into their silo, but their disappearance will not entail any kind of surrender. Whether we can survive that deeper cultural severance is an open question. Like confederates after the Civil War re-emerging years later to fuel Jim Crow and the Klan, or the defeated ghost of the Soviet Union bursting from the chest of a diminished Russia in the form of Putin, the ghost of MAGA will certainly have more to say.