‘The Peripheral’ plays it safe with William Gibson’s future thinking

Reading Time: 6 minutes In some ways, the opening scene of The Terminator (1984) had to have come as a relief to its first audiences. Gritty, darkly lit, with text grimly informing us that this was the city of Los Angeles in 2029, it showed us tank treads crushing human skulls beneath a machine-domi

In some ways, the opening scene of The Terminator (1984) had to have come as a relief to its first audiences. Gritty, darkly lit, with text grimly informing us that this was the city of Los Angeles in 2029, it showed us tank treads crushing human skulls beneath a machine-dominated gray skyline, with lasers and explosions marking humanity’s struggle against a cruel external force. In the middle of the Cold War, amid fears of human beings impulsively pressing buttons to set off a nuclear winter, how could that not be at least somewhat cheering? The idea that something else might be responsible for our ruin, for once?

The idea of collective human resistance against external foes is a bit quaint today, though. Technology hasn’t given us SkyNet so much as the mediocrity of social media as an eroding force in our democracies, as in our economies. You just know that, even if we did create a SkyNet tomorrow, there would still be bitter political in-fighting among all the humans trying to save themselves from it.

The future is messy, and anyone who strives to predict it cleanly is selling short the strangeness of reality.

Thankfully, science fiction writer William Gibson has never been one for making that error. 1984 also saw the publication of Neuromancer, an early and highly acclaimed work of cyberpunk that established a bleak future driven by mega-corporations, with a twisty, noirish plot involving cyberspace, hacker underworlds, and massive drug conspiracies. Tacitly built into this aesthetic was also a fear of Western decline, our cultures consumed by rising Eastern giants of industry, and questions about what a human would be or look like in a world where technology can estrange us from any sense of community not formed by capitalist design.

The messy futures of Gibson’s The Peripheral

Gibson went on to write less dramatic science fiction of the present and near-future, but he’s never shied from the messiness of human beings. Pattern Recognition (2003), set in 2002, used all the tech of its day to highlight the uncanny nature of the internet and its forums: the information we unwittingly share and the deeper patterns of sociopolitical intrigue they inform. And The Peripheral (2014) offered not one but two messy futures, along with a web of others not centered in the plot—though others show up in the sequel, Agency (2020), which imagines an alternate 2017.

Indeed, some consider The Peripheral to be a challenging read, because of how fully Gibson inhabits his near-future rural US timeline. The slang runs thick at first, but it’s really only ever covering a range of technologies and life experiences adjacent to our own: poverty amid unevenly distributed tech possibilities (3D printers, drones, VR), military vets struggling with the traumatic fallout of “haptics” (tech-brain interfaces), religious extremism spilling into armed conflict, and healthcare monopolies.

But critical to the book, which is now also an Amazon Prime series that aired its first episode on October 21, is another layer of complexity: a second, far-flung future in which half its action plays out. In London around the turn of the 22nd century, the world has been emptied by ruinous climate change, political, and economic events, which wiped out most of humanity and natural animal species. Concurrently, though, scientific breakthroughs continued, creating a post-apocalypse filled with tech-driven efficiencies and intrigues for the survivors: many of whom move through the remaining world like disaffected oligarchs absent a playground of underlings.

Luckily for them, some of these new technologies allow them to communicate with the past through VR. The connection works both ways, too, allowing people from the past to patch in and operate “peripherals”, bodies or drones, in the future. Worried about causality? No need: if a timeline deviates, it simply becomes a “stub” branching out from the timeline leading to one’s own future. And the best part, for people in the future? Because of the two-way connection, it’s possible to monetize the heck out of those stubs: to use them for R&D and to amass political power.

Because everything always comes back to techno-finance games, doesn’t it?

In SF as in the real world.

Which is maybe why Amazon Prime was the perfect(ly ironic) home for an adaptation.

The Peripheral, on Amazon Prime

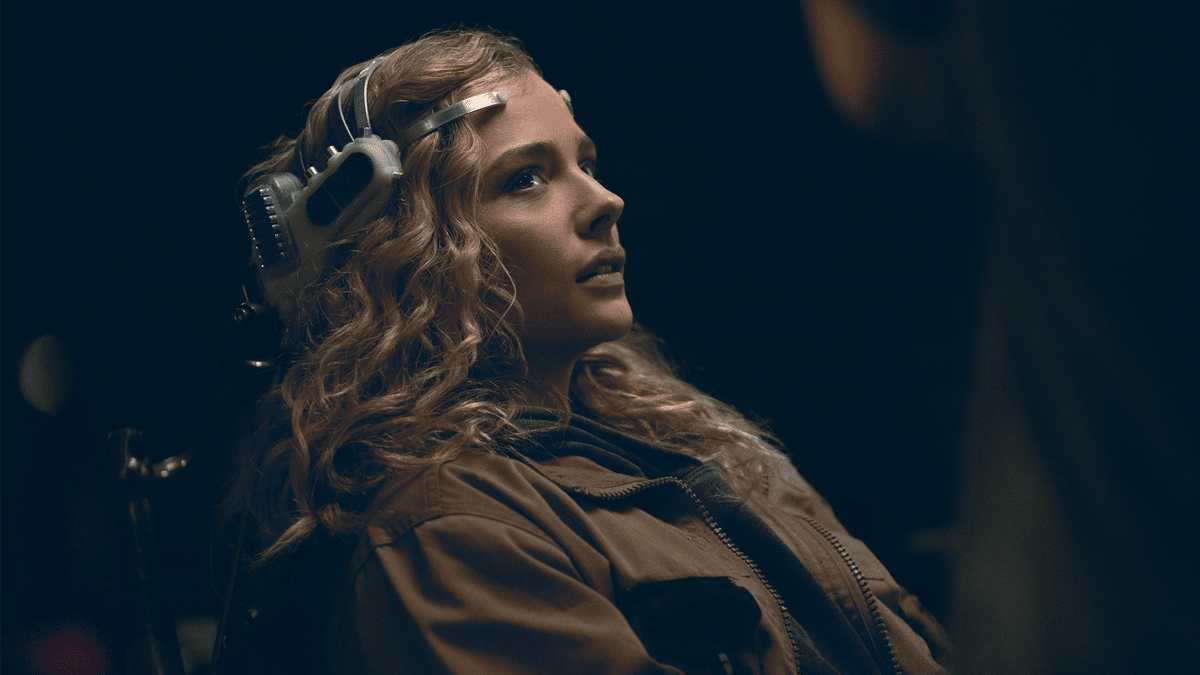

You can see the mark of Westworld producers Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan on this high-budget series right out the gate, in how they’ve chosen to depict Flynne Fisher and the near-future world of 2032 in which she lives. “Clean” is the best descriptor for both. I suspect they were hoping to repeat the success of Dolores Abernathy (sweet-faced, dreamy-eyed, relentlessly abused android in Westworld‘s wild-west amusement park) with Chloë Grace Moretz, who plays a version of Flynne who’s effortlessly good at gaming and fixing the messes made by everyone else at the 3D-printing shop where she works—but prefers simple, honest living in the real world to all the supposedly childish, escapist nonsense of modern technology.

It’s an immediate deviation from the pragmatic and unflinching depiction of life in many parts of the rural US that Gibson’s book embraces. Yes, we still have Flynne’s brother, Burton, a war vet with damage from the haptics implanted for service. Yes, we still also have his fellow vets, including Conner, an amputee who plays a significant role in the book. And we still have an ailing mother who needs medications priced out of easy reach for most suffering US citizens.

But in Gibson’s version, Burton steps out from his main work as VR security for a big, mysterious corporation to fight a dangerous group of religious extremists in his region. Flynne covers for him on the VR front, sees something she shouldn’t, and gets drawn into future-politics when a hit is put out on them to cover the future’s tracks. It’s a version of this tale where Burton’s crew aren’t all goofy gamer layabouts, but rather, fellow hard-done-by human beings trapped in a tough lower-income existence all too common in many parts of the US, as in the world.

Some plot streamlining is of course to be expected in any adaptation, but Amazon’s “baddies” now include a pretty generic local gang of drug pushers who try to get Flynne to service them for access to her mother’s much-needed medication, before Conner comes to the rescue. Gone is the religious extremism and general political cynicism that pressingly informs so much of today’s US discourse. Gone, too, is the sense that, while Burton is suffering from brain damage from his time in the military, he and his friends still live in an ongoing state of conflict to protect their home. Even the economic insecurity that seemed to guide Flynne’s every waking moment in the book has been replaced by a far sleepier rhythm of mostly decent small-town life.

In other words, Flynne and her local associates have been “classed up”, with the staging of Amazon’s version only vaguely gesturing at all the real challenges of rural-poor US life. And this takes away from another potent aspect of Gibson’s original text: the stark contrast between an empty far-future populated by upper-middle-class technocrats, and the stressful rhythm of lower-class life in a world uncomfortably close to our own. In the book, far-future characters express a patronizing affection for our chaotic era, as a “simpler” time before so much was forever lost in the Jackpot. This is a key tonal disconnect for the struggles that unfold, too, because everyone in Flynne’s era has enough on their plates before factoring in future assassins playing their own technocrat games with an already difficult status quo.

The future is messy, and anyone who strives to predict it cleanly is selling short the strangeness of reality.

The futurism we need today

US entertainment generally falters when it comes to depicting class issues well, so perhaps the cleanness of Amazon Prime’s The Peripheral shouldn’t come as a surprise. It does, however, create a mightily de-fanged version of a story that had a lot of potential to reflect the many serious problems we face today. The impact of climate change. The brutal role of corporate monopolies and techno-oligarchies in shaping our economic and healthcare fortunes. Stark disparities in life outcome even amid the rise of new technologies. The ongoing consequences of treating military vets as disposable tools. The danger of extremist movements amid the utter collapse of social confidence in traditional political orders.

In 1984, it was easy to imagine a future where machines try to wipe us out, and also a future where more quotidian market forces bring us to techno-dystopian ruin.

Today, as the saying goes, it remains easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism—but really, at this point I’d just settle for a critique of either concept that’s allowed to keep its bite.