The end of the world is not what you think

Reading Time: 3 minutes Every year of the calendar, for ages and ages, up to and including this year, religious people have believed the end of the world is coming soon. But the end never comes. I would evince a high degree of vanity to think the end of the world will occur in my life span. The whol

Every year of the calendar, for ages and ages, up to and including this year, religious people have believed the end of the world is coming soon.

But the end never comes.

I would evince a high degree of vanity to think the end of the world will occur in my life span. The whole panoply of world history comes to an end in my life? That would make me pretty special indeed. That might also mean my worldview would be dramatically and cataclysmically affirmed as the correct interpretation of all things. I might even dodge death.

Every few decades a few true-blue end-timers rid themselves of possessions, quit jobs, travel to remote spots, and wait. Because the end is coming on Tuesday. Then Tuesday comes. And what happens next? Wednesday happens. Wednesday, every time.

Why must the world come to an end if you are a religious person? Isn’t it enough that your own singular life comes to an end? If you are so desirous to see the otherworld, to see God, to see predeceased loved ones, to see the saints of old, you may do so any day through the portal of death. You don’t need to take the entire world with you in an awful en-time firestorm.

Keep in mind that the end-of-the-world idea is a literary invention. Ancient writers used numerous literary devices like verisimilitude, allegory, hyperbole, metaphor, and symbol, to dream up the end of the world.

As with so many other opinions emerging from a misunderstanding of religious literature, end-of-the-world belief is yet another instance of readers lacking literary sophistication, because the end of the world in religious literature is not really about the end of the world at all.

In religious literature, a story about the beginning of the world—called etiology—is not really about the actual beginning of the world. And a story about the end of the world—called eschatology— is not really about the actual end of the world.

Origin stories are not about the past at all. They are not eyewitness reportage, they are not history, and they are not diary entries detailing actual bygone events. Similarly, end-time stories are not about the future at all. They are not predictions, they are not vaticinations, and they are not crystal-ball visionary statements.

If religious stories of beginnings are not about the past, and if religious stories of endings are not about the future, then what time period are these stories about?

The answer is that these stories are really about the present. Any present time. The stories are fictive efforts offered as instructions for a present moment.

Religious stories of beginnings often describe utopias past—perfect places that serve to indict any present moment as morally inferior and needing correction. These utopias did not exist in the past. There was no Eden. But as fictional stories of a perfect past, they serve as utopic indictments of the present.

Religious stories of the end of the world often describe horrific dystopias—morally tainted places that serve to indict any present moment as risking the slick slope to ethical oblivion. Depictions of these dystopias are instructive fiction, not windows on actual future events.

Taking these stories literally misses the point of their literary art. The authors who conjured these stories knew they weren’t depicting actual events, and the authors never intended the stories to be taken literally.

What, then, is the literal end of the world?

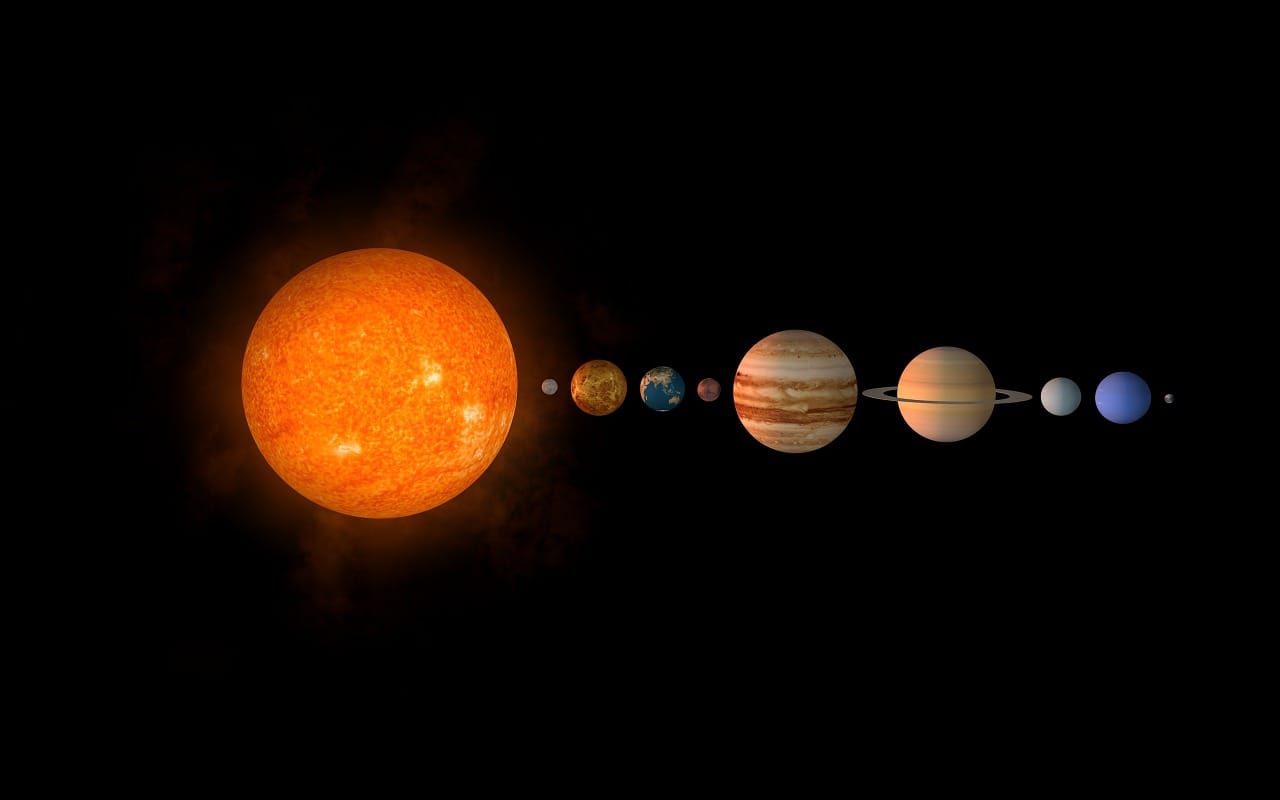

The literal end of our world is five billion years out, timed to the dramatic convulsions of our sun, at which point our brother and sister planets—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn Uranus, Neptune—will also meet their end. Homo sapiens will be long gone by then.

Ten billion years of existence will have been a good run for Mother Earth, who will have kept all our remains to herself, bequeathing them at last to a beneficent furnace called sol, solle, sonne, zon, sun, and a thousand other names.

In the meanwhile, we humans can make the moral most of our mere-near-century of oxygenated existence. And in the years we draw breath, we can love the other sentient beings who overlap our time on earth, and we can value the present (with a view to the future and a consideration for the past). And we can laugh tenderly at all those presuming to see an end where there can only be more beginnings.