On ‘tomorrow sorrow’: How we grieve the future today

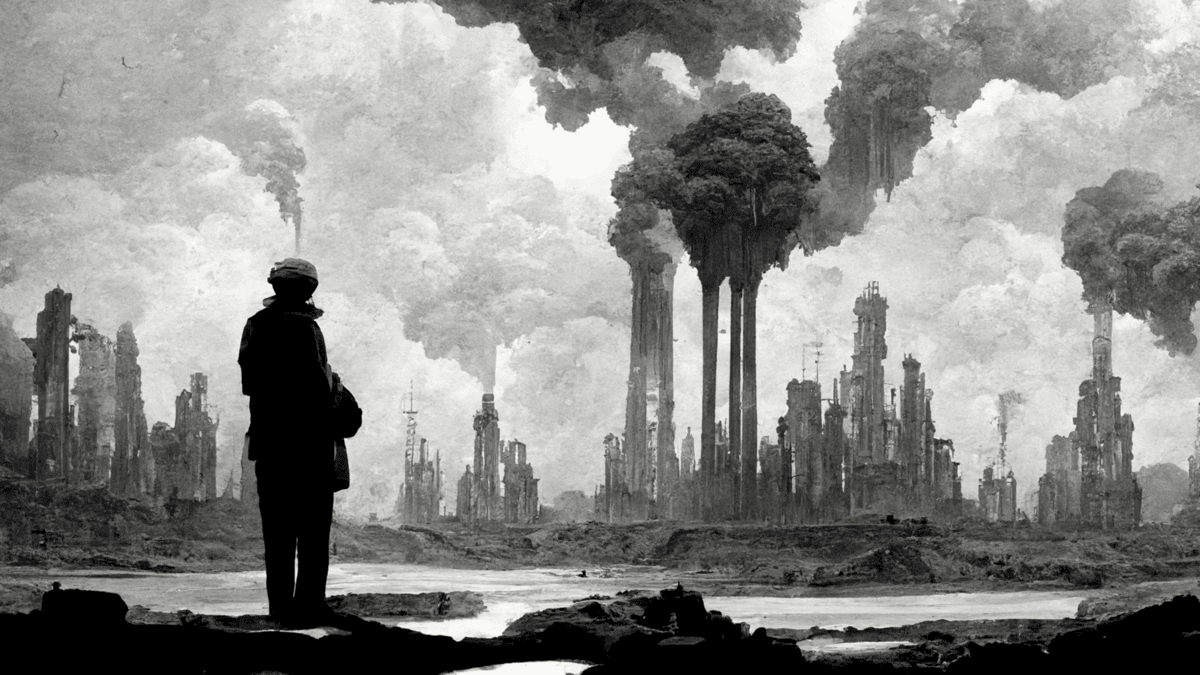

Humans have the capacity to grieve the world ahead, knowing how much is going wrong today. But tomorrow sorrow can make us stronger actors.

I was six years old when Star Trek: The Next Generation first aired one of its most beloved episodes, “The Inner Light.” In it, Captain Jean-Luc Picard wakes to a life not his own. He lives in a small village, where he works as an iron weaver, and everyone explains that he is recovering from a fever-dream.

Picard spends 40 years in this realm, and in that time discovers that his people are doomed: a supernova will wipe them out. They don’t have the tech to escape, but in his old age, his children’s generation launches a rocket, with memories of their people that a visitor might experience. That’s when Picard remembers himself, and wakes on the Enterprise, where he’s only been unconscious for hours. And yet, after all his “years” away, Picard now knows how to play the flute of this long-dead people, which had been sent along with their memorial message. Their song lives on, in him.

It’s a beautiful, haunting story. But what do you think a child might focus on, when watching? I focused on the children. One grandchild, to be specific: the offspring of the people who launched the rocket—a child born into a world that his parents knew was doomed. It would be years before I fully understood the why of it: why bring children into a dying world? Why create life that one knew would be wiped out?

Today, I know many adults who both love their children and regret bringing them into this world, which faces such catastrophe from climate change. I also know parents who believe the world is filled with challenges that require the defiance of hope that having a child represents. And I know many people like me, who will have no children of their own for any number of reasons—including environmental.

But none of us needs to have children of our own to imagine the world ahead, and to grieve for its inhabitants today. To look upon the latest news of international war and vindictive state politics, of corporate monopolies and all the harm they’ve wrought, and feel some twist of sadness that we won’t be able to remedy it all.

And yet, tomorrow sorrow isn’t about giving up. It doesn’t abandon hope.

Quite the opposite.

It’s a deepening of empathy not just for fellow human beings alive today, but also for all the humans we’ll never get to know. It’s the supreme stretching of our global humanism, to include a globe that no longer has us in it. And it’s something we human beings have done, with great resilience, in many hard times before our own.

All living things make some note of their environment, but not all life has the ability to choose what it will focus on: The limits of its imagination. The ambition of its reach.

Nazim Hikmet “On Living”

If you’re a lover of the classics, you already understand what it means to live in conversation with other generations, even if only in our heads. Every time we pick up a book, sit awhile with a painting, listen to a symphony, or walk in the shadows of splendid architecture from centuries past, we carry forward the work of people who never knew us, and never could have. People who were in turn creating art in conversation with the work of other dreamers come before.

Did those writers and artists (and designers, and inventors, and statesmen) dream of being known by some vague idea of future generations while they toiled? Perhaps. The hope of leaving a legacy has certainly inspired many in their work.

If so, though, we who labor in the world today are not much different. We all carry some vague idea of what future generations will look like, even if not all of us feel the same ache to leave them with a better world than we fear we ever will.

Thus does our tomorrow sorrow bind us to similar in the past.

One of my favorite poets, for instance, is a man who spent much of his life in prison or exile. Nazim Hikmet, born in 1902, was a Turkish writer and a leftist dreamer. The latter brought him to leave Turkey in 1921, to explore the new Leninist experiment in the Soviet Union. There, he leaned into artistic futurism, an approach to philosophy and art that celebrated innovation, modernity, and a repudiation of the past in favor of rushing toward a better future.

Imagine the confusing thrill of that era: so uncannily similar to our own, a hundred years on! Back then, too, citizens were just emerging from a pandemic, and an ugly war that had gone on longer than expected, and they were also trying to make sense of dramatic Russian upheavals both remote and with far-reaching global consequences. Then, too, the world was just waking to the possibilities of new technology. Radio! Film! Cars! Airplanes! Modern manufacturing production lines!

In everything, there was a new speed to life, for better and for worse. Faster news, and a faster spread of media sensations. Faster transport for people and products—and faster build-times for those products, too. To some, we were surely hurtling toward a new beginning, on the cusp of tech-utopia. To others, there was only dread. We’d just seen the impact of new weaponry on the battlefield. What else would we be capable of, if technology and new societal arrangements continued to sprint ahead?

Hikmet’s ambitious thinking about the future also brought him to wrestle with the past, to try to inspire people in the present. He first returned to Turkey in 1924, but with no success: his experimental poetry and political views shocked traditionalists, and found little quarter. After his second attempt in 1928, though, he entered his most productive period, as a voice of resistance against Turkey’s rising nationalist fervor. Throughout the ’30s, he tried to reshape his argument for a better future through history—even though his books were banned, and although an epic poem about a fifteenth-century revolution landed him in jail. In 1938 he was found guilty of sedition for such texts, and received a 28-year prison sentence.

Ten years into that sentence, he wrote my favorite poem of his: “On Living”. Radical joy leaps out from many of his prison-era writings, but none quite captures the ambitious scope of his humanism as succinctly as lines like these:

Let's say we're in prison and close to fifty, and we have eighteen more years, say, before the iron doors will open. We'll still live with the outside, with its people and animals, struggle and wind— I mean with the outside beyond the walls. [...] This earth will grow cold one day, not like a block of ice or a dead cloud even but like an empty walnut it will roll along in pitch-black space . . . You must grieve for this right now —you have to feel this sorrow now— for the world must be loved this much if you're going to say "I lived"...

Because that’s just it, isn’t it?

We came from stardust, and to stardust we—and everything we’ve ever known and loved, hated or merely chanced upon, unfeeling—will one day soon return.

But in the interim, we exist as brief witnesses to the cosmos, and that power to bear witness is what makes us so extraordinary. All living things make some note of their environment, but not all life has the ability to choose what it will focus on: The limits of its imagination. The ambition of its reach.

We do.

So what will we choose?

Tomorrow sorrow as a strength in the present

Obviously, not everyone feels tomorrow sorrow. Just as every generation has its dreamers, people who grieve the losses ahead and strive to leave behind the best they can, so too does every generation have its doomsday delighters: people eager for the end-times, and hostile toward anyone who would try to delay their arrival.

Somewhere in the middle, we also have those who recognize that there will be future generations, but see no value in them. Such nihilists cause no end of trouble for the rest of us, especially when they secure important roles in business as in politics. Such people would surely see tomorrow sorrow as sentimental nonsense: a form of self-pity that wastes time we could be spending “getting ours” instead. And yes, many of them will live easy lives with what they “got”, irrespective of its cost to others, and without ever reaping any obvious negative consequences for it.

But so what?

Why waste our fleeting time alive letting such people live rent-free in our heads?

The strength of tomorrow sorrow is that it allows us to build found-family from the past, the present, and the future. We don’t need to define ourselves solely in opposition to people who do not share our wish for a kinder world ahead. Instead, we can lean on similar longings from the past, and today’s dread for all the struggles yet to come, when shaping our sense of self and moral action here and now.

There’s freedom in that re-frame, too.

Freedom, because instead of fixating on people who’ve chosen to spend their time alive disrupting others’ attempts to do better, we can focus on the message we want our words and deeds to convey to those who lie ahead. (And if dissenters come around when they see our vision realized? All the better, but still—a secondary win.)

We can decide, that is, to direct our grief into something bigger than “Gee, we’re awfully sorry we left so much unfinished, and that so much came to ruin on our watch.” Even if that is true. Even if we could’ve, would’ve, should’ve done more.

Because, yes:

The world is undergoing climate crisis with cascade failures the future will endure.

The world is undergoing wars and related violence that will take decades to heal.

The world is reverting to toxic nationalisms other generations will be left to undo.

But we who recognize the power of tomorrow sorrow will grieve all of this—and with that grief plant trees, sow the seeds of better policy, cultivate more robust communities of care, and seek to use the fruits of further innovation well.

For we know that the world must be loved this much.

And in us, at least, it is.