Mother-daughter stories are easy. You just have to break the universe

Reading Time: 5 minutes More than ever before, adult children are breaking ties with their parents. Shifting cultural norms and expectations, coupled with increased individualism and awareness of mental health concepts, are prompting children in their 30s to go “limited contact/no contact” with pare

More than ever before, adult children are breaking ties with their parents. Shifting cultural norms and expectations, coupled with increased individualism and awareness of mental health concepts, are prompting children in their 30s to go “limited contact/no contact” with parents, and learn techniques like “gray-rocking” to communicate with parents who trigger emotional breakdowns and irrational reactions.

Recent media reflects this phenomenon: the second seasons of TV series Undone and Russian Doll (Amazon and Netflix respectively), and the movie Everything Everywhere All At Once, all center on difficult parent-child relationships—specifically, between adult daughters and their mothers. They also share another theme: multiple dimensions, timelines, and universes.

It’s not surprising that themes of time travel and the multiverse are so prevalent in these media. For both parents and their estranged adult children, the gaps in understanding seem to stem from two very different experiences of the same time period. Moreover, millennial children and their baby-boomer parents grew up with such different values that they may as well be from two different worlds. As Joshua Coleman wrote in The Atlantic last year,

[P]arents and adult children seem to be looking at the past and present through very different eyes. Estranged parents often tell me that their adult child is rewriting the history of their childhood […] Adult children frequently say the parent is gaslighting them by not acknowledging the harm they caused or are still causing […] Both sides often fail to recognize how profoundly the rules of family life have changed over the past half- century.

In Season 1 of Undone, daughter Alma attempted to bring her father back from the dead using shamanistic magic that the viewer struggles to differentiate from psychosis. In Seasons 2, she realizes she’s succeeded. Arriving in a new timeline in which her father never died and her sister Becca is happily married, Alma discovers that this time, it’s her mother Camila whose past is riddled with secrets. And in this timeline, it’s golden-child Becca, the one who (unlike rebellious Alma) has never stood up to their mother, who has special abilities. Becca is able to pull both of them into a dreamy between-world with a locked door representing the truth their mother has tried to hide. Becca is hesitant to embrace her powers and delve into her mother’s past, but ultimately agrees that secrecy is hurting Camila’s mental health and tearing their family apart.

Devoutly religious Camila is loath to discuss topics that could cause shame or embarrassment, so it takes the full force of Becca’s newfound powers and a sisters’ trip to Mexico to uncover her secret: she has a son the rest of the family doesn’t know about. It’s clear that Camila would have carried this secret to her grave, stricken with guilt and anxiety the whole time. In Undone, shame and Christian piety prevent mother and daughters from connecting; it takes timeline-hopping, interdimensional travel, and indigenous magic to break through the barrier.

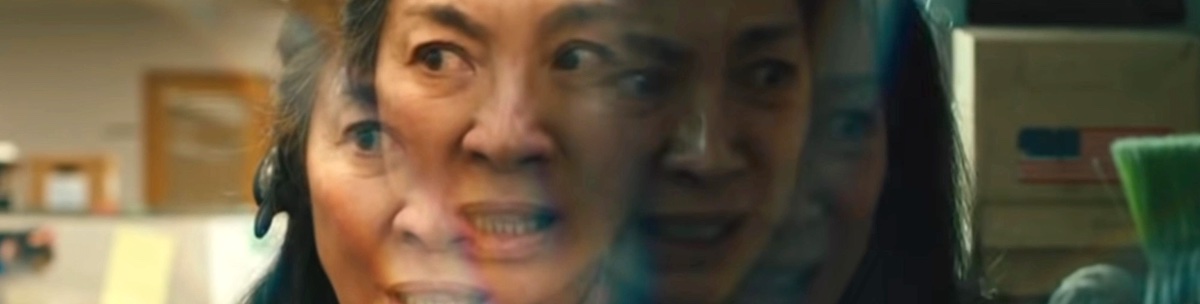

Some of the same limitations form the dramatic core of Everything Everywhere All At Once. The rigid tradition that prevents protagonist Evelyn from connecting with and accepting her daughter Joy is recognizable to many children of immigrant parents, but it’s not solely a product of Evelyn’s own belief system: rather, it’s been imposed on her by her father. Joy, a lesbian, asks her mother to introduce her girlfriend to her grandfather as such; Evelyn refuses, insisting that he won’t understand. At the beginning of the film, Evelyn lacks agency, the plotline of her life buffeted by financial chaos, intellectual and creative failure to launch, and her father’s looming expectations. Meanwhile, the only option long-suffering Joy can see for living her own life is to withdraw from her mother entirely.

Mother and daughter seem doomed to resign themselves to these limited lives until an alternate-dimension version of Evelyn’s husband Waymond explodes into the narrative and reveals that in nearly every other possible universe, Evelyn is skilled and powerful; moreover, the entire multiverse is at risk of destruction by an antagonist supervillain who turns out to be Joy herself. Unlike this universe’s Evelyn, the alternate Evelyns have purpose and are self-actualized, and don’t back down from a difficult conversation. Unlike this universe’s Joy, supervillain “Jobu Tupacki” is vibrant and assertive, confidently glowing in fabulous glitter and costumes. Throughout their epic multiversal martial arts battle, Evelyn and Joy achieve something that seemed impossible in a flat single dimension: they talk about it.

The magic in EEAAO is extensive and dramatic, but ultimately, its purpose is small and intimate: it takes a jolt of existential proportions for Joy to create a persona that can get through to her mother, and for Evelyn to realize that there are possibilities beyond the corner into which she’s painted herself.

Russian Doll’s Nadia, whose mother died long before the show’s events unfold, holds a complex bitterness and resentment for a mother whose psychosis made her an unreliable caretaker. Specifically, her mother Lenora spent or misplaced their family’s precious fortune: 150 gold Krugerrand coins, carefully stashed during the Holocaust and recovered by Nadia’s grandmother, which if not lost by Nadia’s mother – would have been worth millions in 2019, when the show takes place.

In Season 2, Nadia discovers that one particular New York subway train serves as a time portal into the 1980s. By taking it, Nadia finds herself transferred into Lenora’s body, and becomes obsessed with making different decisions and preserving the Kruggerands. It’s painfully obvious to the audience that, while keeping the family’s wealth is a compelling motivation in and of itself, it isn’t the only (or even the primary) thing Nadia would change about her past via her mother: Season 1 included heartrending scenes of the neglect and chaos inflicted on young Nadia by a delusional, probably schizophrenic mother incapable of providing adequate care.

Try as she might, Nadia can’t seem to correct her mother’s mistakes. She returns to the ‘80s time and again, but each time, her plans are thwarted, and the Kruggerands go missing. At the same time, inhabiting her mother’s body reveals to Nadia the chaos Lenora experienced. To Lenora, her delusions certainly felt like reality, and Nadia-Lenora expands her empathy for her mother as she’s met with alternating contempt and condescension from everyone in her life.

(If I could choose any sort of magic to save my own relationship with my mother, it would probably be this kind: a Freaky-Friday body switch allowing us both to understand each other better, to see ourselves through one another’s eyes.)

In the end, Nadia accepts that she can’t undo her mother’s mistakes any more than Lenora could have. With this comes a certain acceptance of her mother herself: Lenora did her best with the decidedly crappy hand she was dealt, and her neglect and mistreatment of young Nadia never came from a place of anything but inept love and good intentions. In a dark twist, however, Nadia also realizes that–by obsessively traveling back in time and abandoning her actual timeline–she’s missed out on her mother figure Ruth’s final days of life. Unable to let go of the unfulfilled desire for her “real mom” to take care of her, Nadia grieves Ruth’s death, understanding too late that the responsible love and protection Ruth afforded would have been enough all along.

What can we take away from these three fantastical treatments of a tragic trend? For daughters estranged from or unable to understand their mothers, it’s not for a lack of desire; the urge to connect is palpable. Religion and rigid tradition (particularly for daughters of immigrant mothers), narcissistic self-absorption–whether a personality trait or a symptom of a genuine mental health disorder–the desire to “save face” and maintain a respectable public persona, and an intergenerational culture clash can feel like insurmountable obstacles to mother-daughter understanding. Shows like Russian Doll and Undone’s recent focus on these themes, and the incredible box-office success of Everything Everywhere All At Once, speak to the fantasy: if we could only hop across timelines and dimensions, perhaps we could reach understanding.

If any readers have a non-magical solution for bridging this divide, millennial daughters are all ears.