How a critical thinking deficit aids fascism…and religion

Reading Time: 5 minutes Why do so many Americans embrace such outlandish and patently false ideas these days? Partly because they were never taught critical-thinking skills.

Because American children aren’t explicitly taught critical-thinking skills throughout their pre-college school years, supernatural religion and other imaginary ideas get undeserved passes from close scrutiny in every generation.

This continuous intellectual deficit has hazardous, self-perpetuating consequences in the U.S. as well as other countries.

Although the term (“critical thinking”) gets bandied about a lot these days in public discourse about education, the irony is that instruction in its essential skills (evidence gathering, logic, etc.) — extant since Aristotle’s time if not before — is still today only implicitly present in American education before college, if at all.

There is no standard elementary- and secondary-school curricula, as for, say, math and science, for the discipline of critical thinking, which applies the empirical, scientific method to all questions, concrete or more ethereal, such as “What are the elements of an atom?” or “Do divinities exist?” or “Are there universes, plural?”

American students are not taught in currently standard curricula to question everything, which is the heart and soul of critical thinking. They are generally taught to accept pre-digested consensus ideas and then regurgitate them back on tests and papers.

The reason critical thinking is not an explicit part of pre-college education is its intrinsic perversity in the context of traditional educational systems and goals, Teachthought.com founder and director Terry Heick wrote in a short but interesting transcript of an interview published on the website, titled “Can We Teach Critical Thinking in Schools.”

“[Critical thinking] is inherently disruptive,” Heick contends. “It requires an approach to pedagogy [educational teaching] that can be unsettling and problematic. And compared to ‘normal learning,’ it can certainly feel like ‘not learning.’”

The problem, she explains, is that critical thinking naturally conflicts with American education’s customary classroom protocols that reflect educators’ “continued infatuation with being both ‘research-based’ and with measuring things.” Not with robust questioning of all “received wisdom,” so to speak, from professors and assigned texts and classroom materials.

“Social planners have no tolerance for [the best and brightest] students, because they may revolt against an establishment that’s out to control them,” author Joe David wrote in a 2018 article published by the Observer, “How the American Education System Suppresses Critical Thinking.”

And if students aren’t taught and encouraged to automatically question everything, even their core beliefs (e.g., Christian dogma), they will be less able to objectively entertain new ideas later in their lives.

That’s my beef. By the time American kids get to university level — and many, many students never get past high school — their core beliefs, if critical-thinking skills aren’t ingrained, are already so deeply embedded in their psyches that new information contrary to what they already believe instinctively will be viewed as threatening — and instantly rejected.

That’s how beliefs work. It’s like spawning trout climbing a waterfall. Many never make it. Writes Lee:

“Critical thinking requires us to be acutely aware of the limits of our normal modes of thinking and suspicious of everything we believe because it knows that without intentional effort and adjustment for all the things we either know badly or don’t know at all, we are at risk of being wrong. And the scale of being wrong is becoming unfathomably large.

“It’s true that uncertainty and patience in thinking and delay in judgment and discursiveness and recursion don’t pair well with education as it is. Refining–or even being aware of–one’s own reality-testing mechanisms is not required to ‘do well in school’ but can be devastating if not ‘done well’ while we live.”

The paramount skill in critical thinking is always being aware of our human capacity to kid ourselves and of our tendency toward self-deception and bias. We need to be able to ask ourselves, “Does this idea that I’ve long believed actually make sense in reality.”

It is a kind of humility, an awareness that reality is complicated and labyrinth and that we are always teetering on the verge of being wrong. You don’t find many evangelicals, for instance, with such humility about their faith, or even doctrinaire atheists, for that matter. Of course, I’m the exception (joke!).

“… [I]f the way we do things can’t facilitate the growth of careful, rational, critical thinking in people who will need to bring this kind of thinking to bear on our biggest challenges and opportunities as a human species, I would say that’s a problem not with the evasiveness, but with the underlying assumptions and designs of formal, western education,” Lee concludes.

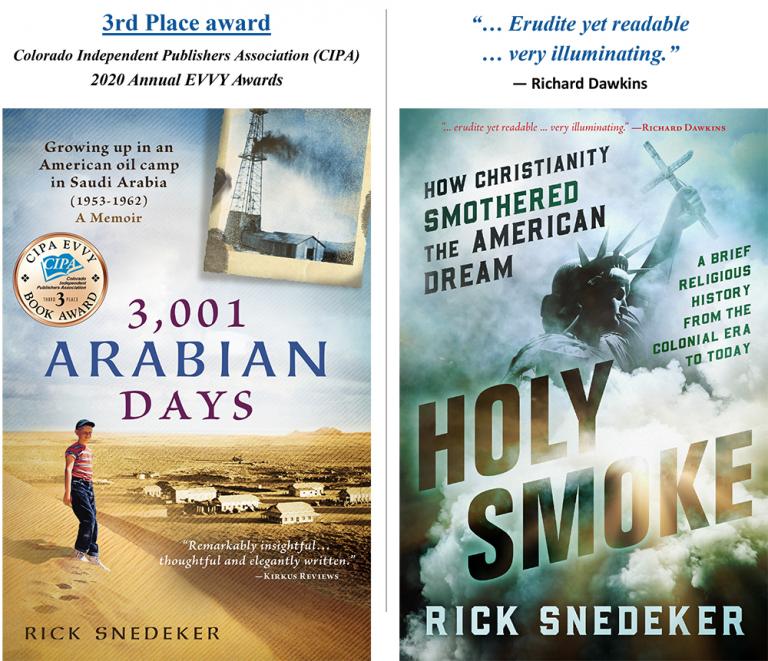

What particularly interests me about Lee’s views is that they promote the centrality of critical thinking in producing rational, responsible members of society, citizens able to fluently sift fact from fantasy and make reasonable decisions and assumptions — the core theme of my 2018 book, Holy Smoke: How Christianity Smothered the True “American Dream.”

In his essay, David laments:

“During my 18 years in public and private schools, I had never felt that I had enough good teachers. Only a few stand out as defenders of clear thinking. The majority, on the other hand, were intellectual robots who expected me to accept biased information, fed by rote and unprocessed critically. If I ever dared to challenge them, they would shoot me down with righteous and noisy disapproval before disgracefully dismissing me.”

He quotes an article by Faulkner University law school professor Adam McLeod, titled “Undoing the Dis-Education of Millennials,” in which he expressed disappointment in the intellectual capacities of many of his students.

“For several years now my students have been mostly Millennials. Contrary to stereotype, I have found that the vast majority of them want to learn,” McLeod wrote. “But true to stereotype, I increasingly find that most of them cannot think, don’t know very much, and are enslaved to their appetites and feelings. Their minds are held hostage in a prison fashioned by elite culture and their undergraduate professors.”

Lee says she regrettably agrees with McLeod’s assessment:

“It is very rare to find a student with a fresh point of view, derived from clear thinking, secured in place by sound knowledge. Too many of them utter popular catchphrases that lack in-depth understanding of the subject. Their minds float around in orbit on some stratospheric level, which is only casually connected to reality.”

They have this deficit because they have not been taught or learned on their own to always and reflexively think critically, to dismiss conspiracy theories peddled as truth. To use evidence-based common sense. And to be wary of extreme improbabilities peddled as fact.

Even the kids see this deficit. In an essay in The Campus, the student newspaper of Allegheny College in Meadville, PA, opinion editor Peyton Britt wrote in March:

“To teach kids information without teaching them how to think [clearly], regardless of whether or not good thinking is rewarded already, is to produce parrots.”

The net result of this educational void in the U.S. over decades if not centuries is that untold millions (perhaps tens of millions) of ostensibly reasonable American adults, who prejudicially emote rather than think critically, still believe in gods and fairies, alien abductions, and QAnon.

This is how religion and other evidence-free concepts get a free pass each generation and put American society at grave risk.

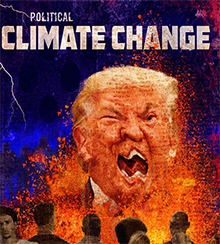

It’s the prime reason we’re experiencing the national crisis of division and mendacity that now threatens us all.

(Image by outtacontext, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)