The second arts and crafts revolution

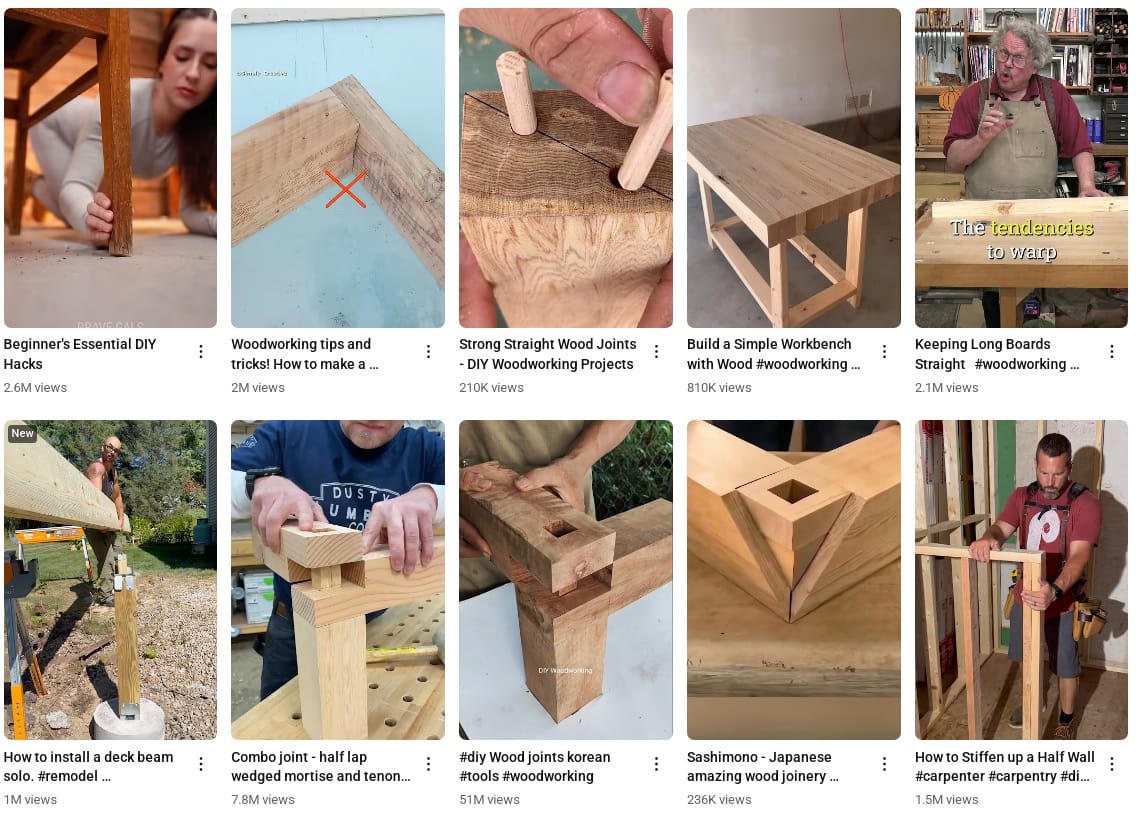

It's never been easier to learn DIY skills.

In a small way, without trumpets blaring or bells ringing, there is a revolution going on. A revolution in arts and crafts. This is a direct result of the internet, and one of the first which is changing our conception of society and human industry.

A reaction to the assembly line

The original Arts and Crafts movement began in the middle of the nineteenth century as a reaction to the industrial revolution. As mass production of goods enabled lower prices and greater distribution, we came to several realizations.

First, it was quickly noticed that having a person perform the same task repeatedly was faster than that person accomplishing a series of different tasks. For example, a high-level look at the tasks to make a ceramic bowl would go something like this: Spin the clay on a potter’s wheel to shape, bisque-fire it, glaze it, then final fire it. If four people did the work, each performing a single one of the above tasks, more bowls could be made than if every person did all four tasks.

Second was standardization. Making the same thing every time is faster than making something different each time. This is true even with decorations. It is faster and easier to make a thousand Wedgwood bowls with the same decoration than it is to make fifty bowls, all with different decoration.

Third was consistent quality. This is interesting because while the industrial revolution generally improved the quality of goods available, simply because there were more of them, in many cases the quality was not as high as that of the previous premium goods. For example, mass production of cutlery sets allowed working class people to afford them, but they were not nearly as ornate as the handmade sets used by the upper class. Similarly, mass produced furniture was much cheaper, but it was also seen as of lower quality than chairs or tables built by a single craftsperson.

While mass production enabled tremendous improvements in the quality of life for large numbers of citizens, the standardization of design and the apparent reduction of quality for some items created a desire for products made by individual craftspeople rather than from an assembly line. This desire continues to this day. Even though the assembly line production process has eliminated the need for craftspeople, some remain to serve the desires of those who want and can afford unique, handcrafted items. There has always been a market for handcrafted items, and there are handcrafted works to suit any budget. From hundred-thousand dollar watches to gimcrack toys sold at roadside stands, we all appreciate and take pleasure in owning something made by a skilled craft worker.

While nothing has changed in our desires, a lot has changed in the manner in which information can be learned.

The DIY revolution

Fifty years ago, when I started to develop an interest in woodworking, there were only a few resources to learn from. Most of them already assumed a basic knowledge of the subject. There were monthly magazines showing pictures of what craftspeople had made, with the occasional dimensional plan to show the sizes and shapes of each piece. It was expected that the reader would know how to make the various joints. It was expected that the reader would know how, where, and when to sand the pieces, and to what grit level. It was expected that the reader would know how to apply the finish, whether it was stain, varnish, urethane, wax, or a combination of them. There were books for beginners, but these were also limited in the amount of information they could contain, and all of them had limitations, information which they simply didn’t have the room to include.

That has changed.

There is an incredible amount of information about the most obscure crafts available to any person with an internet connection. Further, the detail of that information, including not only advice but arguments about what works best, is almost fractal. For example, all the companies which make wood stains have created videos showing how to prepare and apply those stains. But there are also videos by independent creators giving additional hints and tips, including comparisons and critiques of every wood finishing product. This exists for all woodworking tools, types of joint, and even style of design. For a person with a specific project in mind, watching eight hours or so of videos of other people making similar projects is enough to avoid many mistakes and successfully create the project they desire. The result will still not be as good as a master woodworker. Yet, it is likely to be successful enough to use, and encourage the neophyte woodworker to continue with other projects.

This is true of every craft and trade.

Want to make your own shoes? There are videos teaching you how. Want to make candles, blow glass, assay different metals, bake bread, construct a Federal Shield-back chair, paint in oil, distill whisky, plant a garden, fell a tree, lay bricks, carve wood with hand tools or power tools? There are dozens to thousands of instructional videos available, at all levels from the beginner to the already skilled. Many of these crafts require specialized equipment—an assaying furnace is not something an apartment dweller is likely to install—but many more can be done on a small scale.

Self-apprenticeship

Two hundred years ago, apprenticeship programs were typically seven years long. A boy would be apprenticed to a trade at the age of anywhere from eleven to thirteen. By the time he was twenty, it was expected that he would have learned and practiced all the secrets of his craft. Girls were usually not formally apprenticed (there were some exceptions), but were expected to learn how to keep house: all the knowledge of cooking, cleaning, mending, and managing the household expenses. Girls were often sent to work in other households as maids in order to get more experience in those tasks.

At the end of their apprenticeship, as part of becoming an acknowledged master of their trade, a man would need to create a “master-work”—an item which demonstrated their skills, and was judged by other masters of their craft. Only then was the apprenticeship completed and the man could call himself a master of the trade.

The internet videos available today will not make any person into a master. Years of developing the muscle memory of how to handle the tools, or exactly what color to look for when melting sugar, or how to lay bricks with only an occasional glance at a plumb line—these skills do not come from watching videos.

However, internet videos can allow a person who aspires to start a hobby, or even to just create a single object, to avoid years of costly mistakes. An even moderately successful creation will encourage a person to make more, because they know they can do better the next time. An abject failure often results in a person feeling that they have no aptitude for such a craft, when the reality is that they don’t yet have the skill to be successful.

The information available through internet videos is sufficient for a person to avoid complete failure, and encourage them to try more projects.

There will always be a place for mass-produced products. No one person, or even one family, can build/assemble/hew/sew/finish/upholster/bake/dye all the items used by a modern household. But there will be—and already is—an increase in people crafting some household items themselves, either because they are used for very specific tasks, or just for the pleasure of making and then handling something they made.

We are entering a second arts and crafts revolution, which will enrich all of our lives.