Sexual networks: Theory and research

Knowing the structure of our social (and sexual) interactions lets us design effective public health policy.

Sex in the future will become more mindful, honest, and open as people become more aware of our actual sexual practices, instead of everyone pretending that we all have sex (or don’t) like we’re “supposed to” while doing whatever we want behind closed doors.

Network theory is a fascinating topic, because basically everything interesting touches on or directly involves networks. Every ecosystem, every brain, every kind of organization is a network—a group of things that are interactively related to each other. And networks can be fractal, in that we find similar patterns that often—but not always—repeat themselves across multiple levels of detail, such as comparing an ecosystem to an organism to a cell.

Most fascinating is how some of the most surprising and interesting properties of networks can emerge from seemingly small elements of chaos, especially in visualizations of how networks evolve over time. Understanding these networks is one of the positive sides of Big Data’s influence in foisting Computational Everything upon academia. Being able to crunch some truly big numbers has afforded us an awareness and perspective that would be computationally impossible to humans in a pre-digital age.

Veritasium recently posted a video on how the famous “six degrees of separation” (of which Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon is a special case) emerge from some surprisingly basic common-sense facts about society. They even have some of those visualizations, commenting on how profoundly beautiful and organic it is to watch a network evolve. It’s great as a refresher on your network theory, or even if you just want to spend a half-hour on something more interesting and edifying than television. Derek Muller interviews Steven Strogatz, who tells an amazing story about how his research bent our understanding of networks around the knee of the curve that led to an explosion in research opportunities, theory development, and practical applications over the last thirty-odd years.

From network theory to teen sex interviews

Strogatz describes the difficulty of finding hardware beefy enough to perform the calculations the team wanted, and how they had to simplify things for the sake of simulations—but those simplifications led to some deep insights that propelled the research forward by leaps and bounds. This was back in 1994, which for reference, was just a few years before my middle-class suburban family got at-home internet. With the perspective of decades, Muller interweaves Strogatz’s story with follow-ups showing how our improved technology has been used to continue advancing our understanding of the field.

Also in 1994, a team of researchers working with Add Health were beginning something unprecedented: attempting to map the complete structure of a sexual network within a Midwest U.S. high school. Their findings were published about a decade after the initial interviews, and became a seminal paper which has been cited over a thousand times in related research across different fields, for as the authors note, “Data describing the complete structural mapping of a romantic/sexual network in an interacting population has not been previously collected, so there is no obvious baseline against which to evaluate whether what we observe is unusual.”

Hold up—how?

How can a bunch of academics get high school students to be honest or truthful about their sexual contacts? Through the magic of audio computer-assisted self-interview technology, AKA “audio-CASI.” A whopping 90% of students completed interviews in school, and over 80% completed additional interviews at home. Respondents listened to questions on earphones and read them on a screen, then typed in their own responses, without researchers directly observing or parents overhearing.

And so 832 high school students were asked a battery of questions designed to get at their actual sexual behaviors over the previous eighteen months, apart from the status-driven “wiggle room” we all gave ourselves as teens. Since teens can’t control where they go or who they associate with to the same extent adults can, and may not have enough life experience to question how they were raised, what “counts” as sex for purposes of the gossip mill has to balance somehow “putting out” while simultaneously “staying virginal,” or “being a ladykiller” without also “being a womanizer.” It’s a complicated balancing act, for any who don’t remember high school.

When it was time to identify with whom they engaged in these activities and when, they listed other students by unique identifier from a class roster, which was computer-generated so that researchers had no direct access to who said what. Thus, the researchers were able to get a nearly-complete and mutually-validated picture of the school’s sexual network over eighteen months of time, without anybody but the students themselves actually knowing who was sleeping with whom. Amazing, right?

OK, but why though?

Their stated purpose was for epidemiology, because STIs have different transmission patterns than rhinovirus and other diseases which follow more random diffusion patterns. I love their example of an airplane flu transfer: neither you nor the airline chose to sit you next to a sneezing person, so your greater risk by proximity to them is a product of random chance, not choice. But we (usually) choose sexual partners on some basis, which (usually) is the only way an STI can transfer.

This is why the researchers had to get so fine-grained with their questions and analysis, in order to be confident their data was meaningful, despite whatever weird ways people euphemize our actions. It matters whether fluid was transferred or not, regardless of the social stakes people attach to meaningful but general language. Many teenagers don’t consider oral or anal sex to be “real sex” because it can’t lead to pregnancy, and thus consider themselves “virgins,” even though any sexual fluid transfer can potentially carry disease, no matter what the differential status-based consequences may be between oral/anal and penile-vaginal intercourse. This is another reason we need comprehensive sex ed for all: so kids don’t think they’ve found risk-free loopholes in sex acts their teachers didn’t specifically describe in class.

Bearman, Stovel, and Moody also explain in the paper that it was crucial to understand the structure of the network based on specific personal connections (just as crucially, numerically anonymized). This is because simply knowing the number of partners someone has tells you very little about their risk level, unless you also know how their partners and metamours behave. (Metamour, or meta, is polyamorese for “your partner’s partner.”) You yourself may have only one partner, but if your single partner has three other partners who in turn all have three different partners each, then the fourteen of you are mutually at higher risk for disease transmission than, e.g., those in a closed sextet (six people all sexually active with each other but no one else). Finally, they also needed the data over time to see how the network evolved.

Fine, what did they find?

Unsurprisingly, the most common network component was a “disjoint dyad”: two people exchanging fluid monogamously, at least with regard to the previous eighteen months. There were 63 such pairs, accounting for 126 students, represented thus in the network diagram:

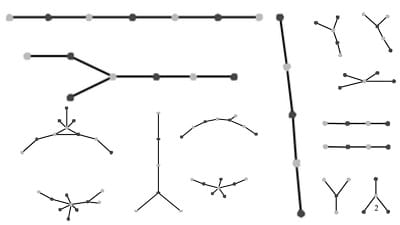

Next most common, there was one case of one boy contacting two girls, who did not contact each other or anyone else over those eighteen months, and nine cases of one girl and two boys in the reverse situation. That’s another 30 students, for 156 total so far.

After that, there were several unique components involving four to fifteen students. Please remember that these groupings do not represent “instances” of sexual contact, but rather fluid contact networks over an eighteen month timespan.

If you really like counting dots, you’ll have noticed that there are only 96 students represented in all of those unique components combined. Which brings our total to 252. There were 832 respondents.

Where are the other 580? Are they all abstinent?

About half of them are, and the other half aren't.

You may wish to sit down for this.

Where are half of the children?

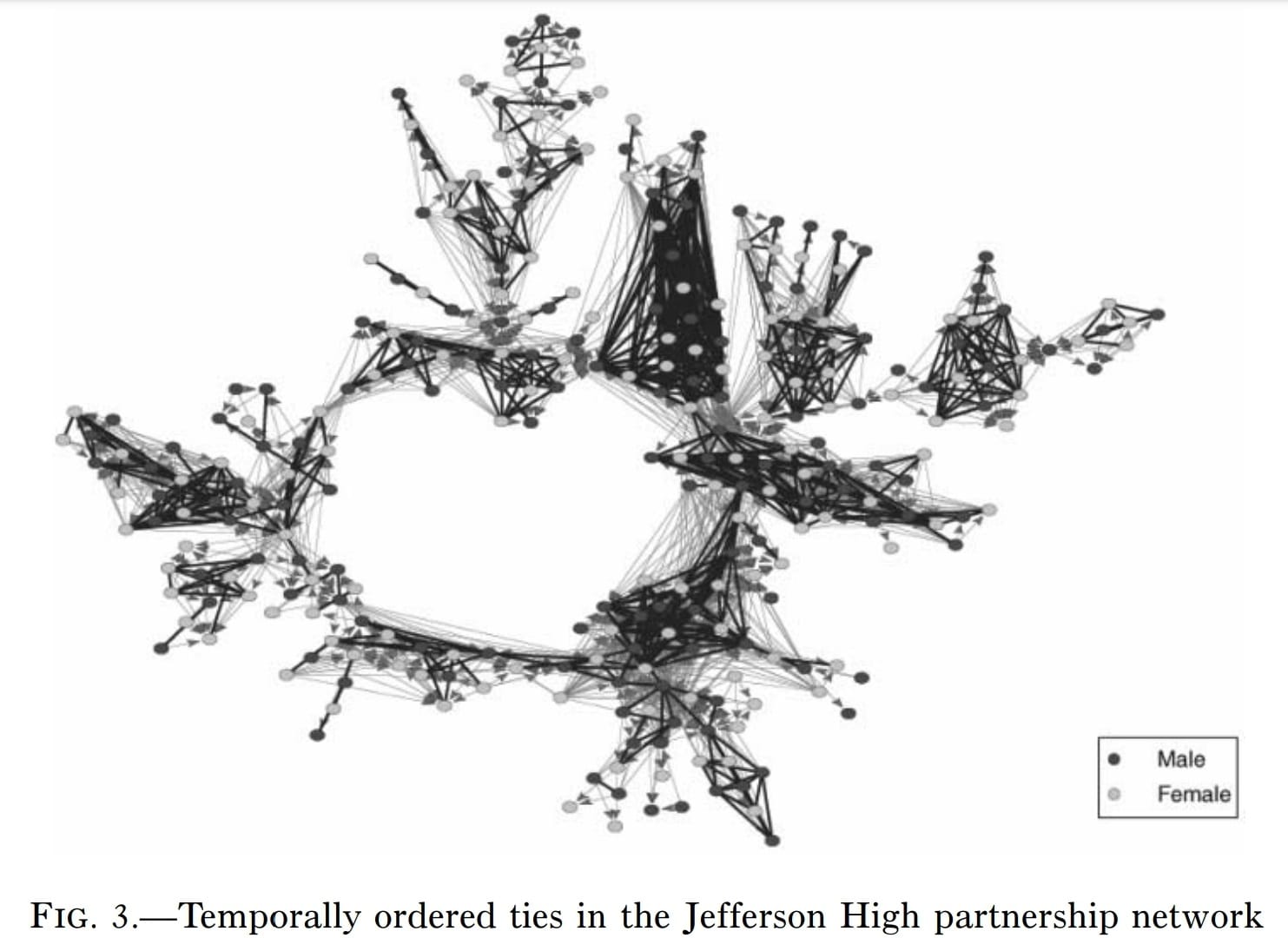

Once again remembering that this is over eighteen months, and these relationships tend to be very short, here is where the other 288 non-abstinent students are: in one gigantic component.

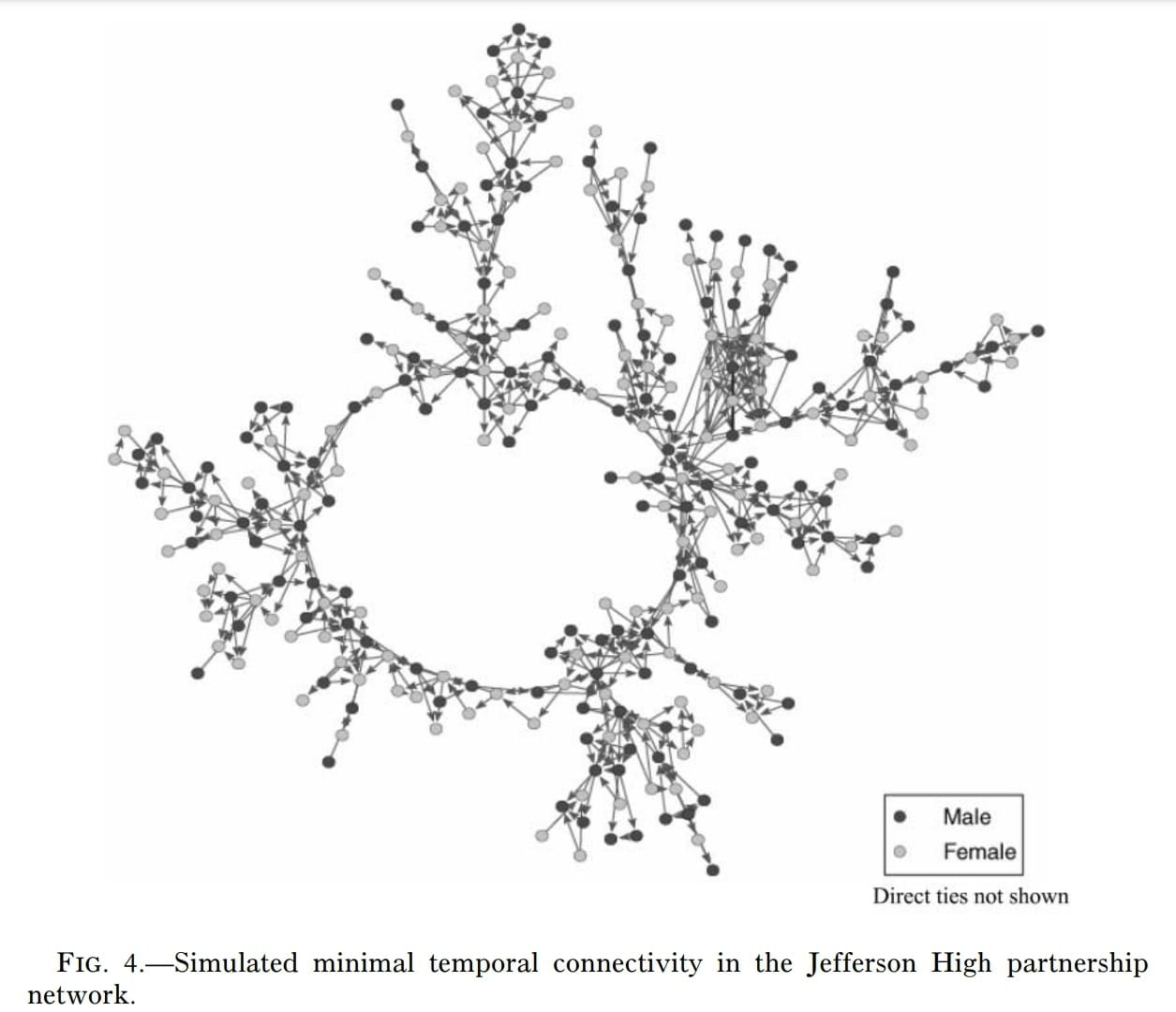

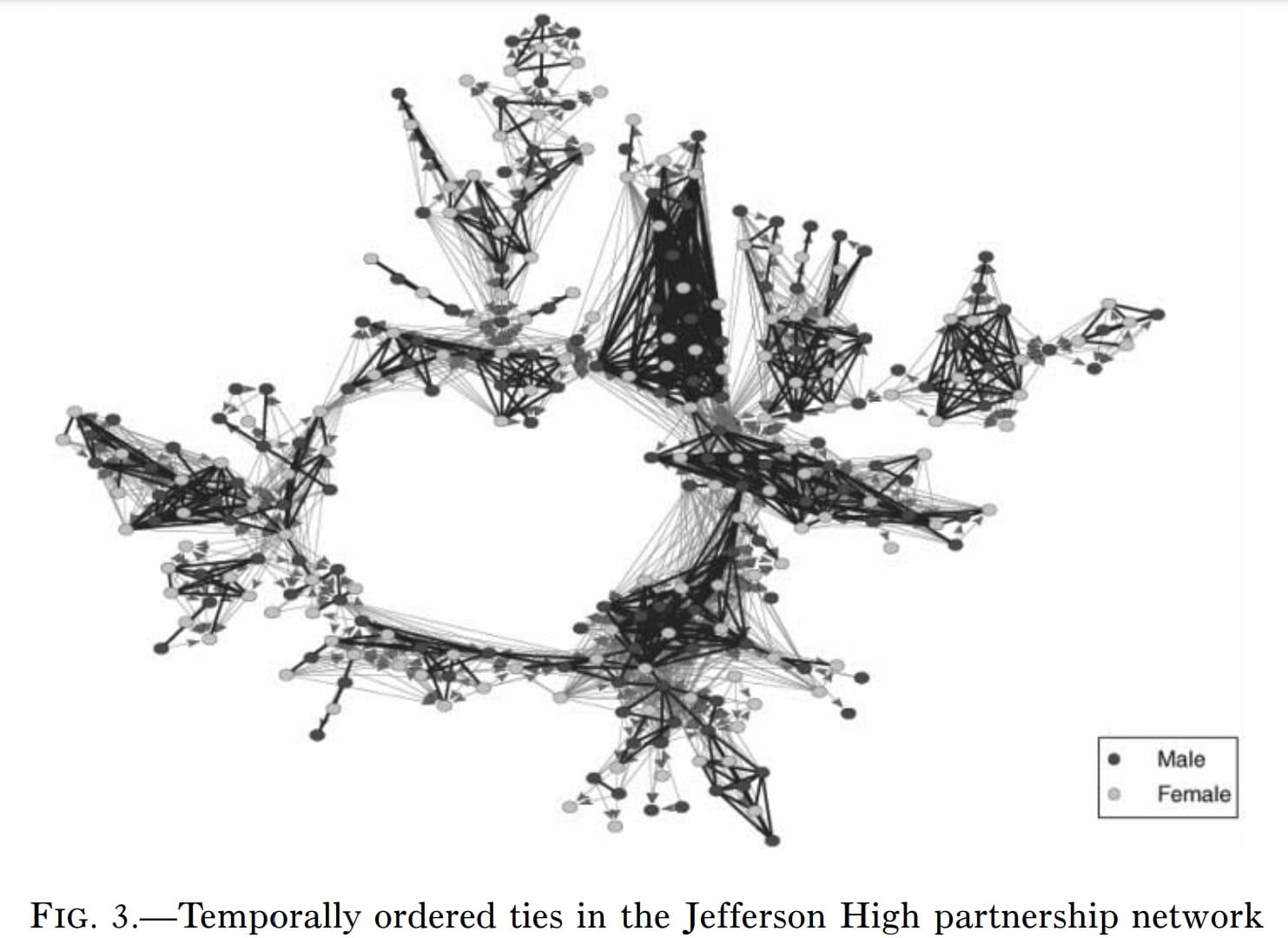

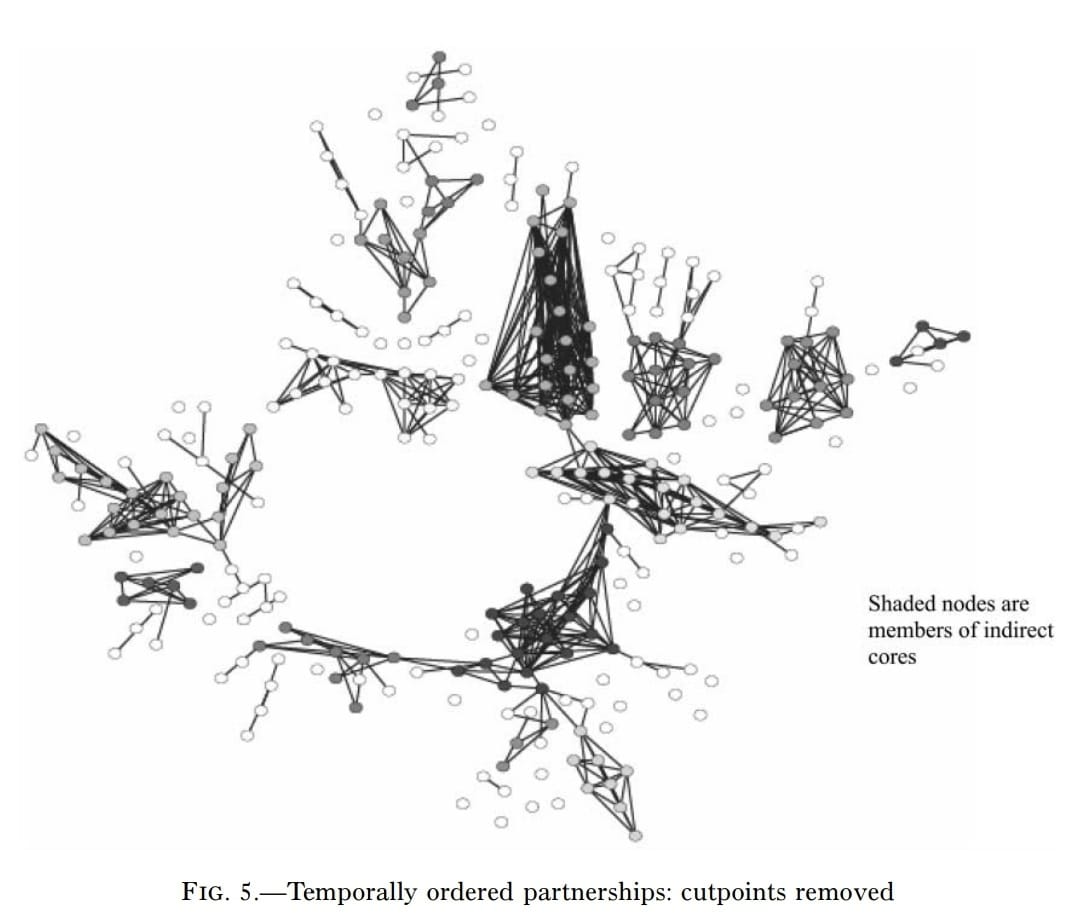

The researchers provided a link to a visualization of how the wreath grows and flows over time, but it’s dead. Still, there’s one cool time-related thing I want to talk about. The researchers added arrows to show the bare minimum of what it would take to get that network to happen, in some kind of order, one connection at a time. Having seen the wreath, this diagram has the same shape, but the added arrows show potential infection vectors.

That’s the most efficient way for every connection to fluid-swap once and make that network shape, and all the indirect infection routes possible while that happens. The below mess is the result of their attempt to show the real arrows that actually made the wreath, and all the indirect infection vectors opened up thereby:

What that complicated pile of arrows probably means is that either these high schoolers had some significant polyamory going on, or there was a lot of “getting back with exes” after allegedly “moving on.”

Fascinating, but what is this for?

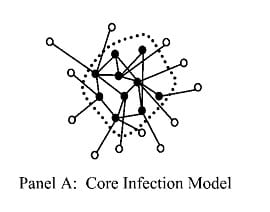

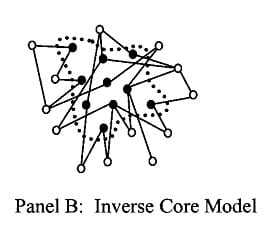

In a word, this is all for epidemiology: to combat the spread of a disease through a network, it is helpful to know how the network is structured and how it functions. Up until now, there had only been three major network models for disease diffusion: core, inverse core, and bridging processes. The authors use clear examples for the first two, which I repeat for their clarity.

A core network can be illustrated by a coterie of needle-sharing IV drug users who sometimes have sex or share needles with those outside their core group. The core functions as an infection reservoir, with members continuously reinfecting each other, and sometimes infecting outsiders who then become vectors to the broader population.

Inverse core networks are illustrated by a group of commercial sex workers (CSWs) frequently contacted by male long-haul truckers. The CSWs and johns can transfer disease between the two populations, but do not (usually) transfer disease within those populations. This being before the time we all started publicly discussing our kinks—erotica book groups, Hear Me Out cakes, comment sections on social media spaces—it may well not have been common knowledge that many male truckers are gay, bi, pan, or trans. I’m not sure, my mom ran with the queer kids in college, so that kind of thing has basically always been on my radar.

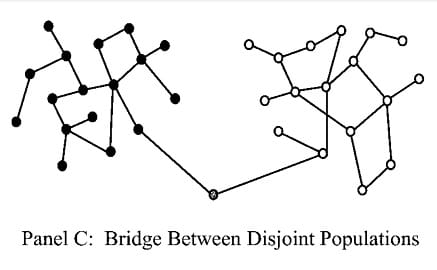

Bridging processes are where two cores are connected by a single (or a few) individual nodes. Historically, this was the form of biphobia expressed by blaming bisexual men (mostly) for spreading HIV from gay men to straight women (“Lesbians don’t get AIDS, they just die of it”). That bigoted scapegoating ignored straight people who use IV drugs and share needles, as well as straight men who solicit CSWs, or straight people who cheat on each other. Any of those behaviors (and more) involve some amount of infection risk, and HIV can lie dormant for over a decade before manifesting, so all of these unmentioned illicit behaviors were tacitly minimized to blame bisexuals.

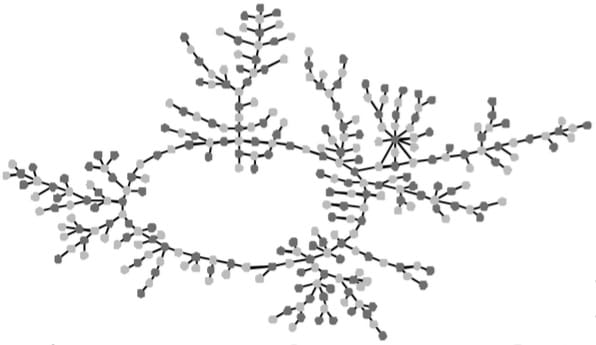

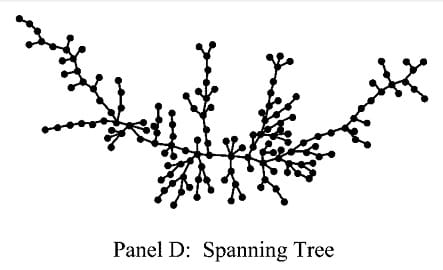

The wreath is a new-at-the-time kind of network called a “spanning tree,” and it has features that make it distinct from the other three. These features have implications for disease control, specifically which kind of public policy interventions will be most effective.

In core networks, what is needed is to break up the entire core until the disease has been extirpated; for example, by treating IV drug users individually in rehab programs where they can all get clean at the same time. For inverse cores, you have to intervene in those outsider interactions; for example, by enforcing condom use in targetable hotspots to directly prevent transmission. In these core cases, the infection is endemic to the reservoir population, but they can be hard to break up because of their redundancy.

However, when you have a spanning tree with no core and little redundancy, then it works more like a series circuit: nearly any cut, anywhere, can disrupt the whole chain. So the best approach here is to try to induce many little breaks in the general population, which is way easier because the casuals can be convinced to tone it down with just a little effort.

The above image shows the cluster version of the wreath, but this time with all single-instance “cutpoints” removed. Notice that there are still some clusters that connect to each other only tenuously, but look how much harder it is for an infection to spread through the entire 288-node component. These public policy approaches are why actual network structure matters, regardless of how squicked out we may be by the idea of how connected we all are in this way.

This covers the background for this month, so next week I’ll discuss some of the stories we can construct from this data (right before Valentine’s!), and I’ll wrap up with how mindful awareness and communication about our sex networks can enhance social trust.