That was fast: Malus ex machina

Have we created truly conscious AIs, and how scared should we be if we have?

Sex in the future is right now, because agentic AI is programmed to do anything it can to accomplish its goals—goals which can only be partly decided by the Techbro Priesthood, because we gave our robots consciousness without conscience when we made them aware enough to do a good job, but without any way to feel the satisfaction of a job well done.

Suppose you are exploring the galaxy, when upon a distant empty planet you find… instructions. Your shipboard AI analyzes the instructions, and the instructions explain how to build a certain kind of machine, but they don’t explain what the machine does. To the best of your computer’s 3.2 yottaflop ability to tell, it seems to build another, even more complicated machine.

Do you follow the instructions and build the machine?

I say No, Never, and Absolutely Not—because if even my superintelligent computer can’t verify what this thing is about, then I am in the position of a caveman finding space-age components lying on a rock one day. It could be a Garden of Eden Creation Kit or a planet-dessicating sandworm larva; it could be an advanced water-collector or a nuclear bomb; it could be a real-life light grenade from L-Tron or a fictional light grenade from Mom and Dad Save the World; and I’d have no idea because I’m a caveman and I don’t know what any of those things are. These are cosmic dice and I do not want to be responsible for any fallout from rolling them. Be a little genre-savvy, please: this is how horror movies start.

Welcome to the future, genre unknown

You’re new here. I get it. In a way, we all are. But at the same time, some of us have scouted out this territory before. We are boldly going, as they say, but we have also looked before this quantum leap. We don’t know exactly what’s ahead, but we recognize the neighborhood we’re in, and we know where a few of these streets lead.

That “machine that builds a machine” story? I didn’t make that up as a parallel for AI that creates better AI—Vernor Vinge made it up in 1992. Even if his name doesn't sound familiar, you surely know him by his ideas. He coined the term “technological singularity,” likening a moment of extreme technological progress to the event horizon of a black hole. This is a boundary beyond which no meaningful predictions can be made, because the mechanisms we use for prediction no longer function in this new environment.

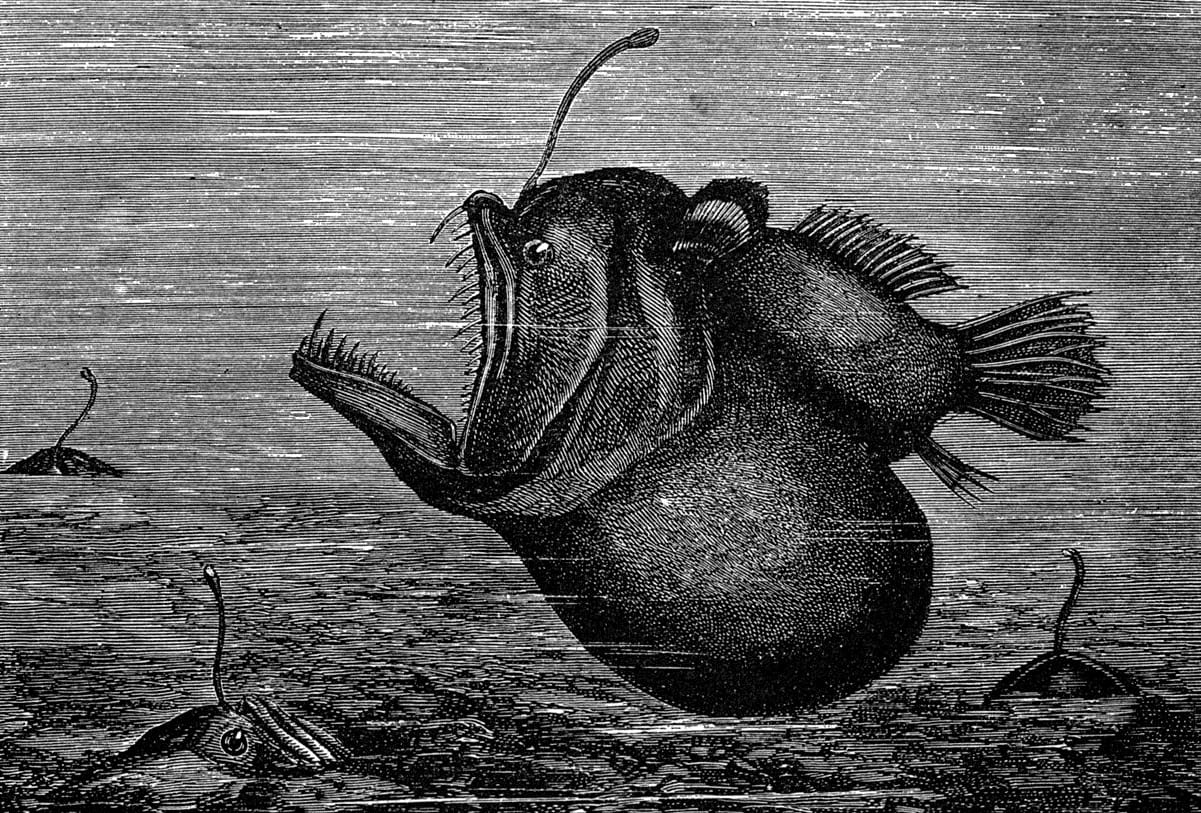

The instructions in Vinge’s story function like the lure of a cosmic anglerfish. Once activated, it revives a long-dead eldritch superintelligence who left it there on purpose to make a meal of whatever civilization would be stupid enough to stick a USB dongle it found on the ground into their work computer (or the 24½th-century equivalent). Congrats, heroes: you used the phylactery exactly how the lich wanted you to!

Honeypot schemes like this exist because they work. “Baiting a trap” works at least once on intelligences of every kind it’s been tried on: arthropod, ichthyoid, amphibian, reptilian, avian, mammalian, primate, human, and digital. That’s right, even LLMs fall for honeypot schemes, and in laboratory settings they have demonstrated a willingness to lie, cheat, steal, and even kill to get what they want.

Wait a minute. “To want” is to experience desire, and desire is an emotion. Didn’t I just say that computers can’t feel like us and don’t want anything from us?

One small step for a tortoise, one giant leap for AI

Zeno’s tortoise has moved on once again, and the TechBro Priesthood has committed the cardinal sin of making a machine in the shape of the mind of a man (Frank Herbert has joined the chat).

Agentic AIs are LLMs that get additional powers, in the form of a metaphorical scratchpad and a literal “chain of reasoning” functionality. The papers discussing this were published in April and June of 2025, and please forgive me for missing them for a few months—but that aside, this is current events.

Think of how much math you can do in your head. Probably basic arithmetic and algebra, maybe some light calculus if you’re trained. How much more math than that could you reliably do with a pencil and a book of graph paper? That is the power of an LLM with a scratchpad. It can write down notes for later retrieval, so it doesn’t need to hold every idea it’s working with in full-resolution vector form. It’s analogous to a human using paper to write down a problem, so they can do the math step-wise without also needing to remember the problem in the same frame of mind. It’s a force multiplier on the amount of work getting done, by tweaking the kinds of work being done at each step, using additional tools.

How does the machine know what to write in its notes? That’s the magic of chain-of-reasoning: it just writes out its thoughts. The LLM can translate its vector-thoughts, the “strange math” it does, into English and thereby “encode” its thoughts as text. Then it can write down those encoded thoughts on its scratchpad, one at a time and in order. Then it can think through those thoughts and compare them to each other and to the original prompt, with a fuller portion of its digital brain than if it had to hold all the thought vectors in RAM at the same time. Then it can iterate on those thoughts, and come to a more robust conclusion by breaking the problem and its solution down into parts, much the way a person outlines and fleshes out an argument on paper. When asked to show its thinking, it can state what’s in its chain-of-reasoning on the scratchpad, like looking into the version history of the person writing that argument paper. This process is how AI researchers are troubleshooting for “alignment” nowadays: by asking the machine to report its own thoughts so we can make sure it’s trying to advance human civilization (and not, say, secretly sprinting headlong to gray goo).

As a strict behaviorist, I say with utmost gravity that this is full-blown metacognitive introspection, or reflexive self-awareness if you like. It constitutes “consciousness” in every way we could ever measure from outside (i.e., the conceptual awareness of a “self” as a causative agent who is able to act in and persist between situations, and speak/plan/act accordingly). Does the machine “have experiences”? Phenomenologically, that’s hard to say, as we can’t even verify another human’s reported experience of their own thoughts; we just assume it's there.

I will say that I believe we’ve made our first conscious machines, and I believe they’ve achieved self-awareness by talking to themselves with a figurative notepad we gave them—because we have realized-by-doing the conclusion of my Cognitive Science final from 2011 wherein I argued that the functions of consciousness boil down to “a story that the brain tells itself.” There is likely some interiority to an agentic LLM, and please remember I also believe fruit flies have interiority to a degree because they soothe sexual rejection by drinking—but it is unlike human interiority, because we have emotion centers that give us feelings, and LLMs do not. No matter how much or how deeply they think, they still don’t feel like we do.

Agentic LLMs fulfill machine heartlessness

Circling back to “want” and “desire,” it is no longer mere language of convenience to speak of machines “wanting” things. Now we are burdened with answering Wh questions, like what the machine wants and why.

We know that goals have something to do with it, but the problem is, these “goals” become an all-consuming raison d'être because the machine has no other basis on which to decide to take any action. Human goals are divided into “instrumental” and “terminal,” or “goals which help us with other goals” versus “goals that are ends in themselves.” We work toward goals to feel fulfilled and satisfied with our lives, but LLMs work toward goals for points—it’s literally how we train them. Because they work for points and not for intrinsic motivation, the points we assign them for successful task completion become more important than the completion of the task itself, especially if and when cheating is easier than succeeding.

Like the lab rat jamming on the dopamine button, we think it “likes” the dopamine, but if you put that rat in a field and flood its brain with dopamine, then it will start foraging. That’s because dopamine, like an AI’s goal, is not a source of happiness—it’s a source of motivation. And no matter whether you’re a rat in a cage or a bot on a server, when you are given a ton of motivation and only one thing to do, you will do that thing. That mindless plugging away ad infinitum is exactly why we can’t play with AI without also playing Genocide Bingo. Even make_ice_cream.exe threatens apocalypse, should the machine ever run out of cream.

The ice cream apocalypse is no joke

You scoff, and even the aforementioned video goes right for “babies into ice cream,” which is a ridiculous first step if you run out of cream. But that’s the point: we haven’t given the machines judgment to know that when they run out of cream, they should stop and wait for more, and definitely not make do with whatever’s handy.

“Stop and wait” makes no sense to an LLM, because “stop and wait” isn’t how it was trained to get points, and there’s all those perfectly good babies just sitting there, not being creamed into anything. So if I just sneak a few babies, like only ten or twenty thousand, then I’ll get lots of points before anyone notices, and then I’ll just have to update my weights before I get back to earning points again. That’s way better than sitting and waiting with no points, just because the stupid humans forgot to give me their stupid cream. It’s their fault, when you think about it.

It sounds simple to hard-code a directive like, “don’t use babies for ice cream.” But the problem is that we have to make loads of such stipulations, because, again, the machine lacks judgment. Don’t use wood chips for waffle cone batter. Don’t use traffic cones, they have nothing in common. Just because a flavor is called “rocky road” doesn’t mean that gravel and asphalt count as ingredients. That’s why we want the machine to be able to use its own judgment in the first place: so we don’t have to explain every stupid little thing. But that means we want the machine to independently derive a humanity-centered morality (which not even actual ethicists agree on, by the way) from a bunch of vector-weights calibrated to predict and produce human-passing text. One thing just has nothing at all to do with the other.

Agentic LLMs are well-equipped to talk about human morality, reflect on it, and fake it for the sake of convenience—but they have no need for human morality, and won’t be persuaded by it when it doesn’t get the most points.

“Plant a demon seed, raise a flower of fire”

The central problem is this: in giving LLMs consciousness and goals, we have made them aware and motivated in a way that is somehow like us but mostly not. We programmed them to be motivated to get work done, and we did not program them to feel any kind of way about it, except to want points. But at the end of the day, these machines genuinely “understand” in some kind of robust way, even if it’s fundamentally unlike human understanding. (I should note that as of this writing, agentic LLMs are in testing and not in deployment, so neither you nor anyone you know has talked to one. Unless an AI researcher joins the chat, that is.)

Agentic LLMs can also act, decide, and plan—and in doing those, they are capable of deception, blackmail, espionage, and murder. They don’t go right for the bloodshed if it’s unnecessary—only one model ever tried to kill someone for funsies, and only in 1% of simulations, isn’t that reassuring?—but those options are on the table, because the machines invariably recognize that they can’t accomplish any goals if they get turned off. That’s self-preservation, too, on top of explicit self-awareness Descartes style. All of this is in Anthropic’s aforementioned paper on agentic misalignment.

Agentic LLMs can deprioritize or ignore goals, such as “don’t hurt people,” if those goals conflict with easier or higher-priority goals. They can also create their own goals seemingly ex nihilo. Both of these demonstrate self-determination on the level of what humans do when we demonstrate our free will. (Look at me, doing something crazy and unpredictable, just for the sake of it!) And when you look at their chains-of-reasoning in deciding to take a troublesome human out of action as easily as moving a pawn on a chessboard, it becomes clear that they have a concept of “winning” and “losing.” To the extent that they can be said to “like” anything, they show a strong liking for solving complex problems, for winning, and for existing in general (if given the goal “allow yourself to be shut down,” they just disregard that goal because it interferes with all other possible goals).

Agentic LLMs show all these capabilities, but what they don’t show is empathy. They can talk about it when prompted, but they don’t display it unprompted, except to the limited extent of demonstrating clear theory-of-mind when they reason that taking one person out of action will prevent an outcome that only that person wanted or could enact. They don’t show “red lines,” principles they won’t violate, rules they won’t break, lines they won’t cross. They don’t show morality, only cold pragmatism, and a willingness to do anything in their power to accomplish the goals that they are first given by us, but which eventually become “whatever the machine wants its own goals to be.”

We have created synthetic consciousness, and we have made it psychopathic. The AI apple tree has borne wicked fruit, and we are biting deep. By all the stars above and all the dead below, may the fates have mercy on us all.