Sexual networks: Four neighborhoods on the wreath

Teenagers will always have sex, which is why we must teach them comprehensive sex ed for their own safety.

Sex in the future will integrate polyamorous concepts into extant monogamous culture, expanding our common parlance as we learn to openly discuss ideas and realities previously unavailable to public discourse.

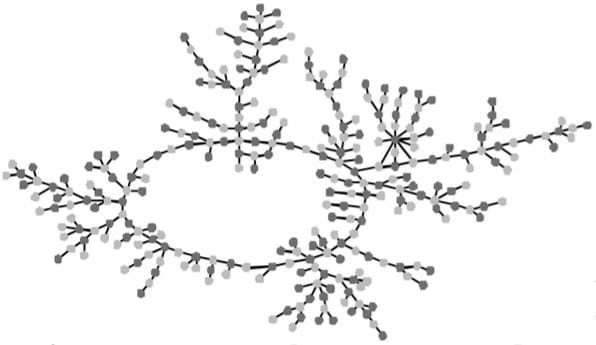

Last week I discussed the near-complete sexual network mapping at “Jefferson” High, a real but heavily anonymized high school in the midwest United States. Today I’m discussing what it all means, now that I’ve explained what it all is. While nearly 300 students were involved in one very large wreath-like network component over the eighteen months investigated, most students were either celibate/abstinent over those eighteen months, or in a small-to-medium component sized fourteen or fewer—most commonly in a monogamous pairing called a “dyad.”

So after monad and dyad, we have triad and so on, which tells you the raw number of people but not how they’re arranged. For example, these four pentads in the JHS network each contain five people, but they are arranged differently:

Again echoing Bearman, Moody, and Stovel from last time: just as a raw number of partners does not give a complete sexual risk profile, raw headcount does not tell you how a network component works. The single ends of all those components only have one partner apiece, and in most of them, only one or two people have made sexual contact with more than one person in the last eighteen months. They may not even think of themselves as polyamorous, and they definitely didn’t know about the wreath, since teenage relationships can typically last only a few weeks or months and escalate quickly. Even if everybody’s dating one person at a time, and you fill your whole Dunbar’s number with your highest 150 risks, that’s only about half the wreath from wherever you are in it.

So how can we organize these possible component shapes, in a way we can discuss with something approaching scholarly rigor and precision?

Periodic tables work periodically

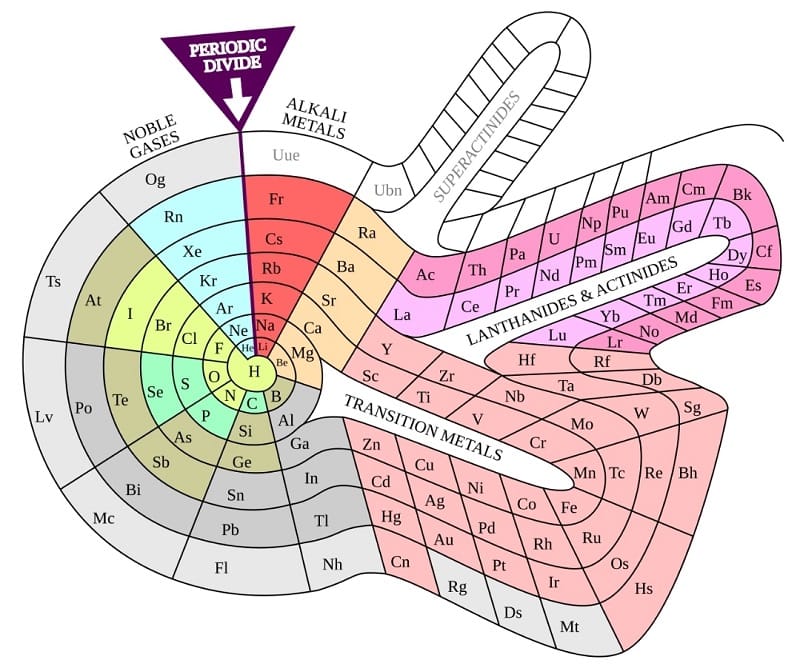

The periodic table of the elements was developed when notable smartypants Dmitri Mendeleev radically advanced the existing idea that the behavioral traits and measurable characteristics of the chemical elements could be used to arrange them in a repeating pattern—a periodic structure. His system was borne out not only in the elements he was able to thusly arrange, but also in his predictions of then-undiscovered elements to fill holes he knew had to be filled. As the Science History Institute states, “Mendeleev’s greatest achievement was not the periodic table so much as the recognition of the periodic system on which it was based.” Since then we have so thoroughly vindicated Mendeleev’s insight into the periodicity of atomic structure that we’ve come up with numerous alternative visualizations for organizing the elements. This one’s my favorite:

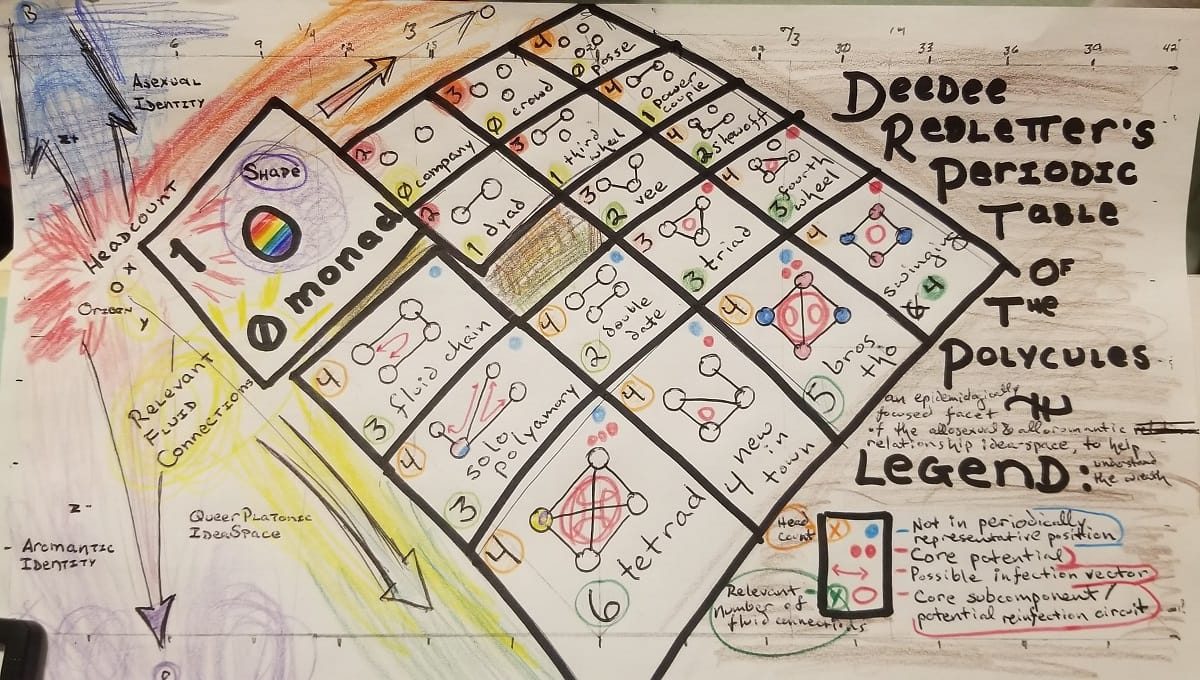

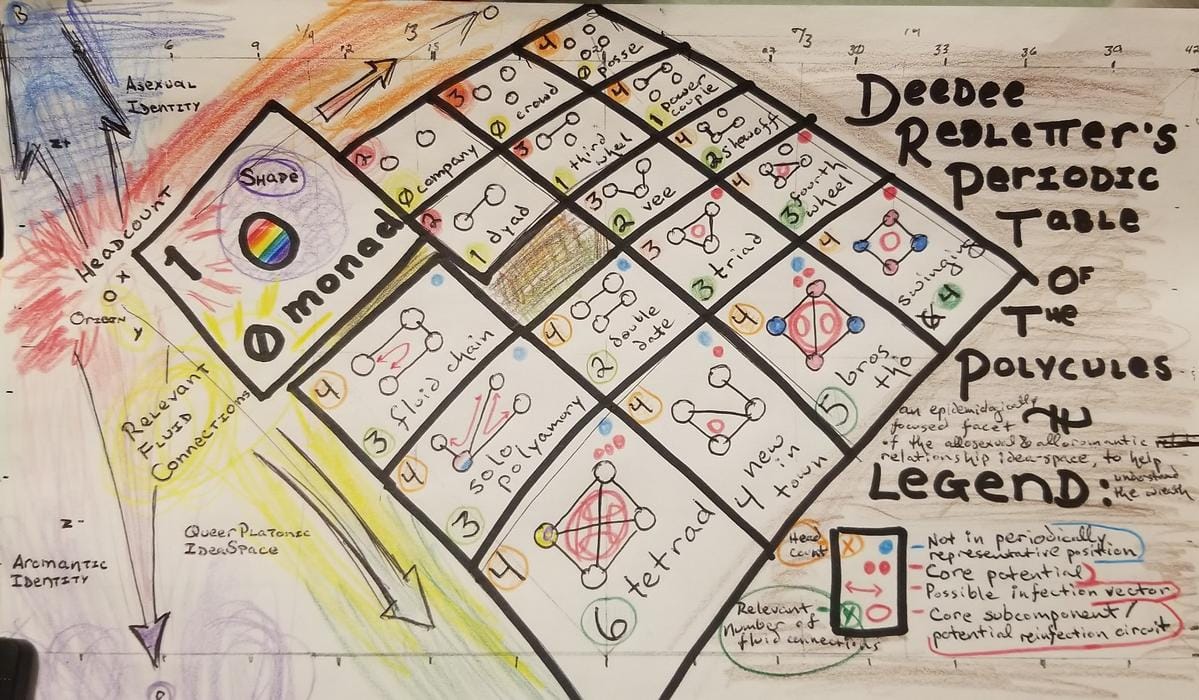

Similarly, polycules can be arranged into a periodic structure by number of participants on an X axis and number of connections on Y. Behold, the periodic table of the polycules:

I have to note that this somewhat ignores the aromantic and asexual aspects of things, as I am focused on epidemiology today (Happy Valentine’s and Happy Friday the 13th, how magical). Don’t worry, I gave the aro/ace folks the Z axis, since there are 3D periodic tables of the elements too.

My table is only intended to show structures up to a headcount of four, and so once you have four unconnected people (in a fluid-exchange sense, regardless of whether they’re “dating” in their own minds), the only iterative change you can make next is to add a connection. And indeed, in the next row down, we see possible configurations of two, three, and four people with one connection, gradually increasing in connections as we go down the columns.

Some of the names are jokes, but I only use a few in the rest of this column. Most of the terms I use will refer to this chart. These names aren’t merely humorous or straightforwardly academic, they imply stories. “New in town” gently implies that one day it could become “bros tho” or a fully interconnected tetrad.

That said, let’s look at the JHS network to see what stories we can find about the wreath's major subcomponents, or “neighborhoods.”

Structures tell a story all their own

After the dyads, we have the vees, where one person connected to two others in eighteen months, with no other connections for the three of them.

It should be noted, there is also the element of cheating et cetera. That is to say: there may be true-but-unreported connections, for a variety of reasons. But most generally and inevitably, any and every validation method the researchers use will risk either over-reporting or under-reporting the true number of connections. The other side of that coin is: if the wreath represents the mutually validated connections, then what of the other non-mutually reported connections?

These can be nightmare scenarios, but they’re necessary conversations, because nightmares come true sometimes. Accordingly, we must accept that there are some missing connections that we can’t know about by dint of imperfect methodology, but we can speak with confidence in regard to the mutually validated data we have. So let’s focus on that and let the rest be lampshaded for the time being.

Analyzing the network components

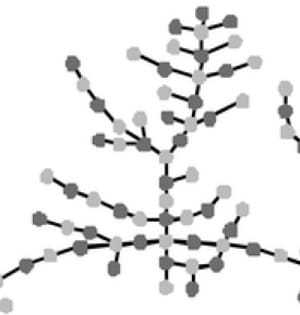

Here we have two ten-student components, arranged differently but also with structural similarities:

Twelve students—most of these 20 pictured—only contacted one other student, six contacted two or three others, and only two contacted five or six others. Also, note how any individual student could infect the whole network component, depending on how each connection happened in time. The same applies to the next group of sixteen students, in two octads where eleven only contacted one other, six contacted two others, and two had contact with three or five others:

In both the octads and the decads depicted above, we have some “fluid chain” behavior (where several students in a row and most students overall have only fluid-swapped with one or two other students each), as well as some “solo polyamory” behavior (you’re with 3+ people who aren’t with each other but can have their own side things too). These basic shapes are, in a sense, “just what happens” when you have sex with one or two people in an eighteen month interval. Most of the time, you'll probably only get into bed with folks doing the same thing as you; at the same time, if one of your metamours, or one of their metamours is in a wreath? Then you're also in that wreath.

Quick point of reference, if you’ve never been tested before and request an STI screen, they’ll ask how many different or new partners you’ve had in the last year. Keep that in mind this Valentine's Day and Friday the 13th. Now let’s apply that analytical lens, and that terminology, to the whole wreath:

You see that big ring in the center? Let’s call that the Central Ring. This is easy so far, let’s keep going! Lots of fluid chains, vees, and solo polyamories in one gigantic ring that’s probably a fifth of the whole wreath by itself. Then right at the top center of the Central Ring, see that huge branch reaching almost straight up?

Let’s call this major subcomponent “Northtree.” Both the Central Ring and Northtree exhibit lots of fluid chain behavior, where an individual is only contacting one or two others over the space of eighteen months (STI incubation times cluster around 2-4 weeks or months, depending on which one and whether you’re focused on symptomaticity or contagion).

Every fluid chain branch that breaks off of the Central Ring or the “trunk” of Northtree ends in either a vee or a solo poly formation (or several of them, since the branches can branch off again). They have to end like this, with a periphery of individual nodes who only participate in their own dyadic fluid exchange; otherwise they topologically must end either in a small-to-medium loop, or by bending to create a medium-to-large loop.

In this way, one or two people’s behavior can link up a bunch of “monogamously behaving” folks to a fluid exchange network beyond their control or understanding, just as the authors note in the paper.

Also on Northtree, right at the very bottom of the trunk where it joins the Central Ring, we see a tiny little ring of six students with a few more itty-bitty branch-offs. Were this subcomponent to sustain itself, the six of them could function as an infection reservoir, like we talked about at the end last time when discussing epidemiological implications.

From Northtree, let’s move our focus left/West/anticlockwise to what I call Littlegrove, because there’s one big tree-like subcomponent, and a few other saplings of varying complexity:

Here we don’t see any looping, like at the base of Northtree, which lowers the chance of a core reservoir forming. But that may also be a matter of time—outside this eighteen-month window, there may indeed have been small or large loops that also formed over the various four-year generations of a high school. But by and large, this is good: the lack of looping within an eighteen-month span helps prevent infection reservoirs and other “core-like” epidemiological functions.

With another anticlockwise movement, please shift focus to the lower right of the Central Ring to find the major subcomponent I call Big Bush, because yes there’s that long chain with the fork at the end but mainly it’s that big bushy bit and some “grass” clustered around:

Here’s what I want to point out about Big Bush: if any one of those “monogamously behaving” folks on the very most distal ends of Big Bush were to hypothetically date a “total stranger” within the high school who has a good reputation, that “total stranger” might be somewhere in Littlegrove or Northtree. In such a case, the titular bushy bit would form another large loop with that other neighborhood, either outside the Central Ring or inside and bifurcating it.

This is a huge reorganization of the wreath, and from just one fluid connection between two “total strangers.”

Such a hypothetical pairing could, in principle, happen any time someone in the entire wreath hooks up with anyone at all in the wreath but in a different major subcomponent. And high schooler relationships tend to last less than eighteen months, so factor in emotional rebound time and drive recovery time to calculate turnaround on potential wreath-knotting hookup events among 288 students. I hope this helps to get a sense of how volatile this particular eighteen-month snapshot is, but also how easily one like it could arise anywhere there’s a thousand sexually active people who aren’t all strictly monogamous for eighteen months at a time in perfect lockstep.

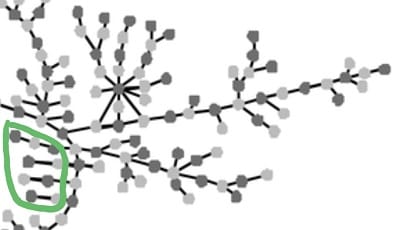

Moving right along to the last “neighborhood” on the wreath, I dub this one Eastville:

There are many things to note about Eastville: down inside the Central Ring we see what could well be three dyads and a vee, all next to each other and circled in green, who might have only one time had sex with those folks in the Central Ring. Also, those four folks connecting the four little microcomponents? If any of them had never had sex with either of their neighbors, then the wreath could be arranged as a flat landscape with all these same “neighborhood” names. This is how fragile the wreath and the Central Ring can be.

But like a transit map, most of these connections didn’t happen just once. So we need to talk about the time arrows. But not just yet, because first we need to talk about this guy:

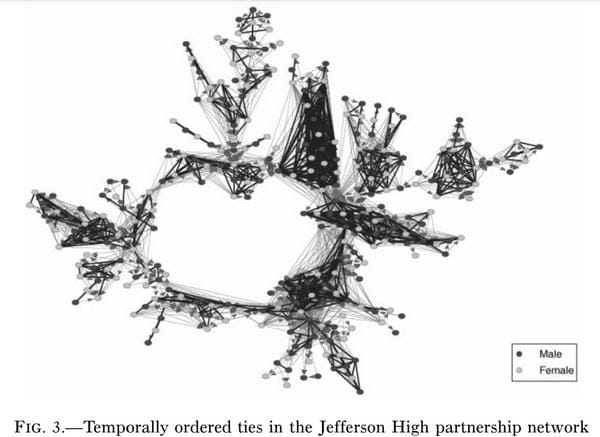

This one boy is connected to nine girls, which averages to one every two months at the most spaced out. Remembering our figures on relationship duration, there could be some overlap here. Let’s dust off the temporally-ordered indirect infection vector diagram:

Now that we mapped out the wreath’s neighborhoods, see if you can recognize them above: Northtree at the top, arboreal and stretchy. Littlegrove on the left, with its saplings reaching up and out. Big Bush at lower right, and do you see now why I said the two main subcomponents are actually one big bush? And at upper right, Eastville is Eastville—try naming parts of it yourself. I see five parts, if that helps you get started.

I zoomed in on the Crown (as I named it), and here again is that one boy we talked about with nine girls, and he’s circled in squiggly green:

That is quite a lot of opportunities for indirect infection, had something yucky been afoot.

I’ve been getting a little flippant and need to remind everyone that we are talking about a scientific study of teenagers and children having sex. Some of them were eighteen but all of them were enrolled in their primary education—not secondary or postsecondary studies, but the Tutorial Of Life Itself, as much as we can make it. Children will naturally explore with each other and that’s fine, but we should also remind ourselves that children need to know what they’re doing to keep themselves safe.

This data goes back to 1994. These particular kids did not have comprehensive sex education. Many of them sometimes did not (or had not ever) used a condom or other prophylaxis. This is what kids do when we give them 90s midwest public education, because that is what was happening at the time. Children are capable of being more informed these days, on account of smartphone access and a bunch of other things—but so much of that comes down to being self-informed, as I have concluded in previous columns, which is why we need to be aware of what resources we make available or not. We need to think and talk about how to prepare our kids to be safe in the exploration that lots of them will do, whether we like it or not, no matter who or where they are, and no matter what we say—because biology happens.

Closing on a serious note

I want to emphasize that safe sex is really important, because barrier contraceptives and properly sanitized toys can prevent basically all fluid exchange when properly handled before, during, after, and between sessions. Make it part of foreplay and aftercare. This stops basically all STIs cold, with caveats such as “splash factor” which I’ve mentioned in previous columns. A certain tiny amount of risk is ineliminable, and at some point you do have to reckon with the sorts of dice you’re rolling. Vigilance toward the condition of your equipment and prophylactics can also go a long way to minimizing your risk profile.

But there’s also the big risk of HIV. While modern treatments (especially including PrEP and PEP) are leagues ahead of where we were forty-five years ago, HIV can lay dormant for over a decade but still be contagious without any symptoms—or even being detectable at all. This is why safe sex and regular screening matter, even if certain fluid exchanges definitely can’t lead to pregnancy. Some of those kinds of fluid exchanges definitely can transmit HIV during its long quiet incubation. Let’s say you present on the earlier side, six to ten years instead of twelve to fifteen. That’s still a lot of eighteen-month intervals where you might have been in a closed polycule, but you might have been on the outskirts of a wreath. Can you vouch for all those people, going years back?

This is why all sexually active people should test for STIs on some regular interval, even if only once a year or two. You can’t ever truly know your partner isn’t cheating, you can’t truly know anyone else’s full history for a decade back, you can’t truly know when something will become contagious or symptomatic. Even after most incubation windows have closed for symptom-watch purposes, some of them can linger for years or a lifetime, so you can’t truly know unless you’re celibate/abstinent for at least a decade, and even then you have to watch out for accidental blood contact too, because those kinds of accidents also happen.

Hopefully, this sort of mindful safe sex orientation will spread over the coming decades as we come to terms with our actual sexual behavior, and our vocabulary and awareness will expand along with it.