Does the rule of law have a future?

Is law objective, or just the preferences of those in power?

Trust in American institutions is plumbing historic lows, and this includes the Supreme Court. There's a widespread perception that the justices are partisan actors who rely on their own personal beliefs rather than the law, and who can't be trusted to act ethically or rule in the best interests of Americans.

Somewhat surprisingly, this view is held by both sides of the political aisle. On the left, people believe the six-justice conservative majority is captive to President Donald Trump and rules in whatever way he needs. On the right, conservatives follow Trump's criticism that the courts are corrupt and biased because they don't rule in his favor often enough.

These polarized views of the Court are a reflection of how partisan we all have become. It is hard for anyone to look at decisions by the Court with dispassion and to separate issues of law from our general policy and political commitments.

Most of us can imagine a different context with a lower political temperature, and a different group of justices, in which it might again become possible to reach decisions based on the law. But what if the problem with judicial decisions is deeper than that?

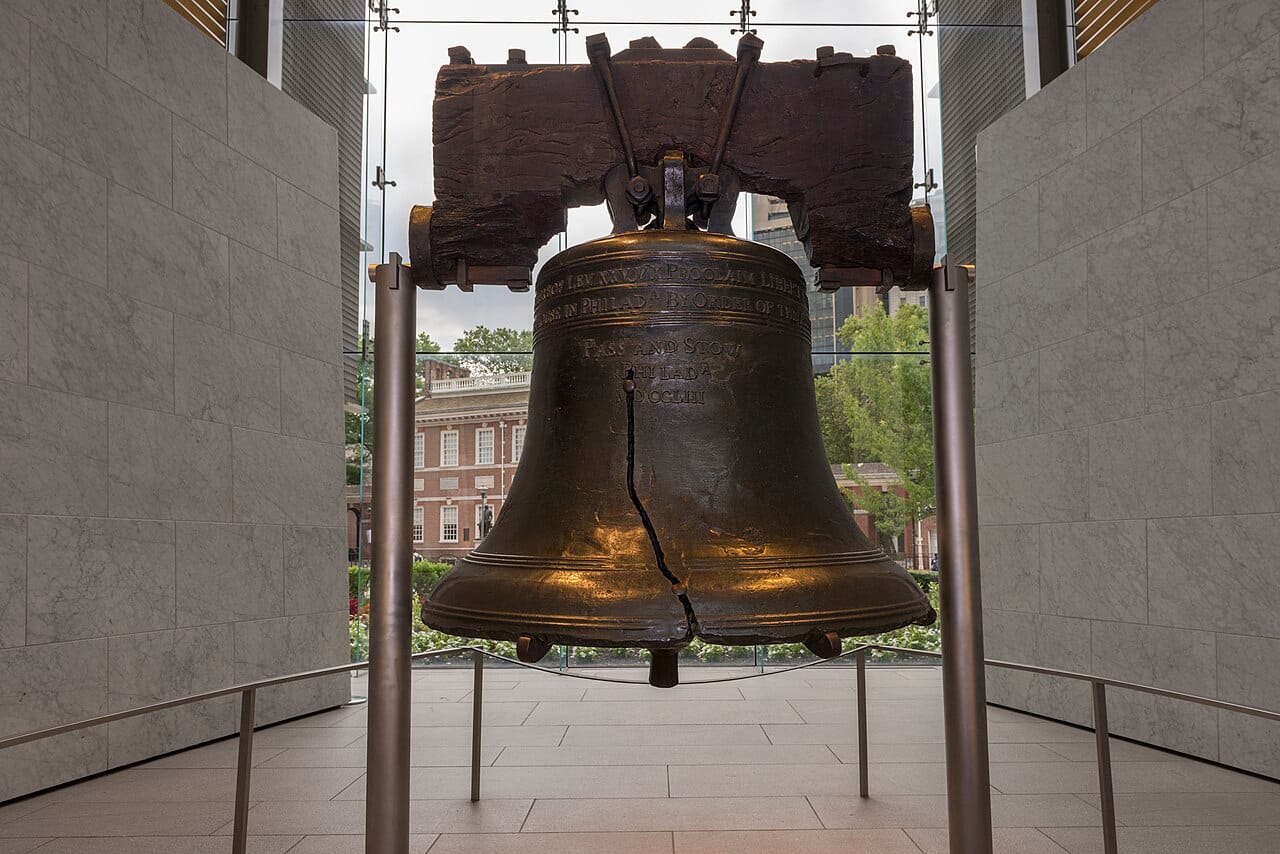

America has always prided itself on following the rule of law. The tradition of an independent judiciary enforcing the rules equally for everyone is a vital source of America’s material prosperity. People perceived it as safe to live here, to buy property, work, invest, or start a business because the law ensured safety and stability for everyone. But what if this idea was always an illusion—and now we know it?

"The life of the law"

The classic case for the rule of law, including judicial review of the constitutionality of government conduct, was that law is a matter of technical judgment, not the personal beliefs of the judge. As Chief Justice John Marshall wrote in 1824, courts had no “will” in legal matters. Years later, Justice Owen Roberts wrote that in deciding whether a statute was constitutional, a judge just had to "lay the article of the Constitution which is invoked beside the statute which is challenged" to see whether the latter conformed to the former.

But, beginning in the 1920s, a movement called Legal Realism arose to challenge this classic view of judicial decision-making. The realists admitted that text, history and precedent could decide many legal issues and were always present in any judicial decision. But, in doubtful cases—and those, of course, are the important cases—these sources don’t point to a definitive answer and judges have to use their own best judgment. This is true in all areas of law that people care enough about to litigate, including constitutional issues.

In those doubtful cases, the realists said that judges base their decisions on their own conception of the public good—using their experience, wisdom and sense of justice. Bad judges do this unconsciously and sometimes corruptly. Good judges are self-conscious and thoughtful about this process. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., put the matter this way in The Common Law in 1881:

The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed.

Legal Realism was a shock to lawyers and the legal system. But it could be accepted in the end because, as the realists pointed out, it had always been the case, in all courts and in all times. Since that was so, it was reassuring that courts had created a reasonably just system. The same seemed to be true of constitutional law. So, why not accept it and continue along that path of progress? Thus, to an extent, Legal Realism was tamed.

Postmodern law and the death of God

In the 1970s, the challenge to the rule of law deepened. The response to Legal Realism had argued that experience, wisdom and justice had led, and could continue to lead, the law in a positive direction.

But this new challenge, associated with postmodern theory, which was itself fueled by the Death of God movement, argued that appeals to these kinds of universal categories were just masks for privilege and power. There were no privileged positions from which to render judgments. Indeed, it might not be possible to consider anything intrinsically just or unjust in any objective sense.

As Yale Law Professor Arthur Leff put it in 1979, “As things now stand, everything is up for grabs.” Therefore, in the inevitable exercise of discretion that Legal Realism had identified, there would be only judicial will, in the sense of Nietzsche’s will to power. Many people feared that this was a kind of nihilism that threatened to destroy the rule of law.

To meet this threat, conservatives in the legal profession proposed new forms of objectivity for law—Textualism and Originalism. The goal was to identify objective meanings for provisions in the constitutional text, based on what the terms meant at the time of their adoption. This eventually became known as “original public meaning.”

But this effort to stem the tide of nihilism eventually failed. Even though the Court had a majority of justices who were publicly associated with Originalism, the justices failed to follow original public meaning when important cases arose. Specifically, in the two key Trump cases before the 2024 presidential election, the Court ruled to keep Trump on the ballot and declared him immune from criminal prosecution, even though original public meaning plainly called for different reasoning and outcomes. If Originalism could not be objective when it counted, it failed to defeat nihilism.

The issue for the future of the rule of law is the same as for many other areas of human endeavor. If everything is up for grabs, how can we preserve some sense of objectivity in value judgments? Are there really rules that everyone follows and that we can rely on to give our lives stability? If not, and if everything is just a power grab, how can we live together when every election might bring life-or-death change?

The legal thinker Lon Fuller gave us the answer we need in his debate with H.L.A. Hart about the meaning of law in 1958. Fuller said it is easier to give reasons for a good result than an evil result.

For example, the statement "slavery is right" is a value judgment. But to defend slavery, one must make all kinds of arguments that are impossible to justify. Of course, the slaveholder will not agree that slavery is wrong. That is why the Civil War had to be fought. But we can see today that arguments for slavery were based on special pleading, not on reason. The arguments against slavery were much stronger. They could not be a perfect demonstration of the injustice of slavery—not in the same sense as a demonstration in mathematics—but they certainly made all the case against slavery that one would reasonably need.

In current debates, we don’t have the benefit of hindsight that we do with slavery. But the slavery example reminds us that there really are true and false—or at least truer and falser—answers to important issues of public policy. There really is justice and injustice. Right and wrong. We just have to make the best arguments we can and, eventually, the better arguments will succeed. That faith is enough to sustain a rule of law. That is, it is enough if we can hold to that faith.