An end in sight for Huntington's disease?

Genetic therapy offers hope for a dreaded and previously untreatable disorder.

[Previous: In vivo gene editing: The medicine of the future]

It's taken years of diligent work, much frustration, and countless failures, but science is finally unlocking the potential of genetic engineering to cure disease.

Our first successes were with blood disorders like sickle-cell, where cells with faulty genes can be extracted and treated in a lab. That was the easiest target, but we've kept progressing, gaining the ability to target more complex and less accessible parts of the body.

Now new discoveries are coming faster and faster. The latest scientific triumph holds out the possibility of curing a particularly awful scourge.

DNA as destiny

The disease in question arises from a mutation in a gene called HTT, which is expressed in the brain and codes for a protein named huntingtin. It's not entirely clear what the protein's normal role is, but we know what happens when it mutates: the fatal disorder called Huntington's disease.

Mutant huntingtin causes damage to nerve cells that accumulates over time until they die off. The symptoms make a dire list: uncontrollable jerky movements called chorea, trouble with balance and walking, slurred speech and trouble swallowing, mood swings, memory lapses and deficits of executive function and reasoning, progressing to dementia, hallucination and eventually death.

Huntington's disease is the paradigm example of DNA as destiny. If you have the defective gene, you're guaranteed to develop the disease. No lifestyle change can prevent it or slow its progression. Huntington's is inevitably fatal. From the first onset of symptoms, typical life expectancy is at most twenty years.

In a cruel twist, Huntington's symptoms often manifest around the age of 40, meaning that most people find out they have the disease only after they've had children who may also be doomed to get it. Worse still, the mutant gene is dominant—so if either parent has it, the chance of a child inheriting it is a full 50%.

Until recently, there was no treatment for Huntington's disease. There was nothing we could do for sufferers. A genetic test could check for the presence of the mutated HTT, but some people questioned the ethics of this, given that it was only informing people of their fate with no ability to prevent it.

Genetic therapy plus brain surgery

Genetic engineering offers the prospect of a cure for Huntington's and many other dire diseases. Scientists are already studying different approaches to the problem.

The problem is that the gene that causes Huntington's is in the DNA of nerve cells, deep inside the brain. Targeting most internal organs is a challenging task as it is. But the brain, which is protected by the blood-brain barrier that blocks most drugs, seems like a nigh-impossible target for genetic therapy.

However, one team of scientists has made a breakthrough. uniQure, a gene therapy company from the Netherlands, has developed an experimental therapy called AMT-130. It's an audacious treatment that combines genetic engineering with brain surgery.

AMT-130 uses an adeno-associated virus or AAV, a harmless virus that's easily engineered to deliver genetic material of our choosing. The hard part is getting it where it needs to go: the striatum, a region deep inside the brain that's involved in motor skills and cognition, and that suffers some of the most severe damage from Huntington's.

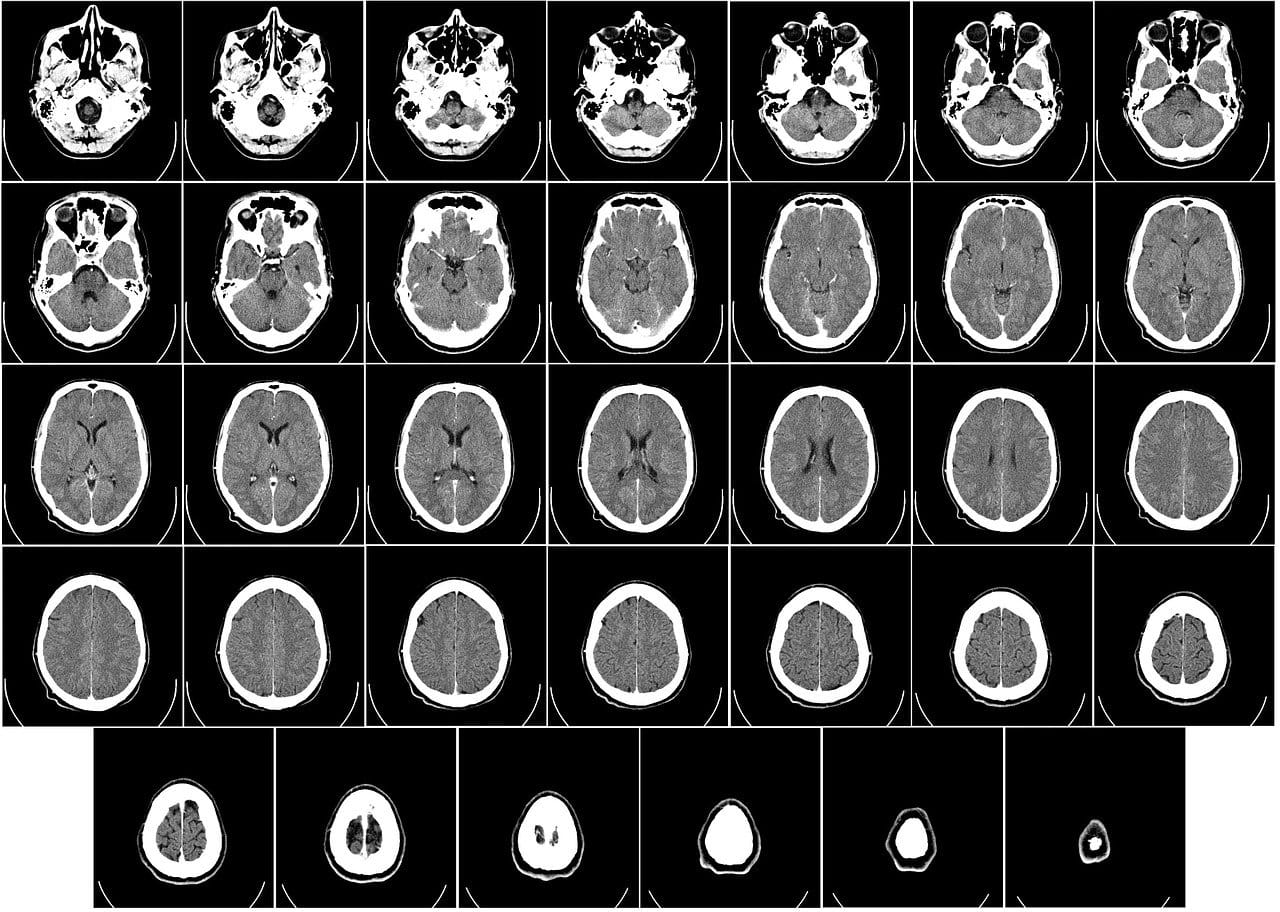

To deliver it, surgeons use a technique called stereotactic surgery. Surgeons use live MRI images to guide probes into the patient's brain, where they release the AAV agent in precisely the right place. Once it enters brain cells, it delivers its cargo.

Normally, an experimental treatment this invasive and risky would be harder to justify on ethical grounds. But in this instance, the inevitability of Huntington's is a perverse blessing. People who have the gene know they'll get the disease, no ifs, ands or buts, so they have less to lose by rolling the dice.

As you may know, DNA is a double-stranded helix that contains the genetic instructions for building proteins. When those instructions are needed, the cell "reads" the DNA and copies it into another molecule, messenger RNA or mRNA, which is a single-stranded relative of DNA. The mRNA is taken up by ribosomes, which translate nucleotide sequences into amino acids.

The cell has regulatory mechanisms that modify this pathway. One of them is called microRNA, a short non-coding RNA sequence that's complementary to a chosen messenger RNA. When a microRNA sequence binds to messenger RNA, it blocks its translation into protein. It's effectively a messenger saying "make less of this".

AMT-130 uses this mechanism. It delivers a microRNA that targets the mutant huntingtin protein, repressing its production. The hope is that, even if it's not a complete cure, it will slow the damage, ameliorate the symptoms, and lengthen the patient's life.

Does it work?

And, based on early results from a clinical trial—it does.

uniQure recruited 29 people who have the gene for Huntington's disease. They received a single dose of AMT-130, then their progress was tracked for three years and compared to a control group who didn't get the therapy. The results speak for themselves:

In today's update, the study team are reporting that people who were given a high dosage of AMT-130 have experienced 75% less disease progression after 36 months as measured by the composite Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale, which incorporates motor, cognitive and functional measures... There was also a statistically significant benefit as measured by another key scale of disease progression, Total Functional Capacity, and in three other measures of motor and cognitive function.

Their levels of NfL, a protein in spinal fluid that's a marker of neuronal damage and disease progress, were lower than at the start of the trial. Normally in Huntington's, these levels would only increase over time. According to Ed Wild, one of the principal investigators, one of the patients in the trial who was medically retired because of Huntington's symptoms has been able to go back to work.

This isn't a full cure, but it's a giant step forward for a disease that previously had no good options. With this therapy and others like it under development, Huntington's sufferers stand to gain many years of life and good health. It's the reclamation of a future that must have seemed as if it had been stolen from them. And one day after that, this disease may be banished entirely. It and others like it will no longer be a death sentence.