63 words that could silence the courts: How a tiny clause in Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” threatens American democracy

Authority without enforcement is theater dressed as law.

Buried on page 562 of the 1,100-page “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” lies a clause so brief and obscure that even trained eyes might miss it. But if signed into law, these 63 words could profoundly alter the balance of power between the three branches of American government—silencing the judiciary’s ability to enforce its orders just when it may be needed most.

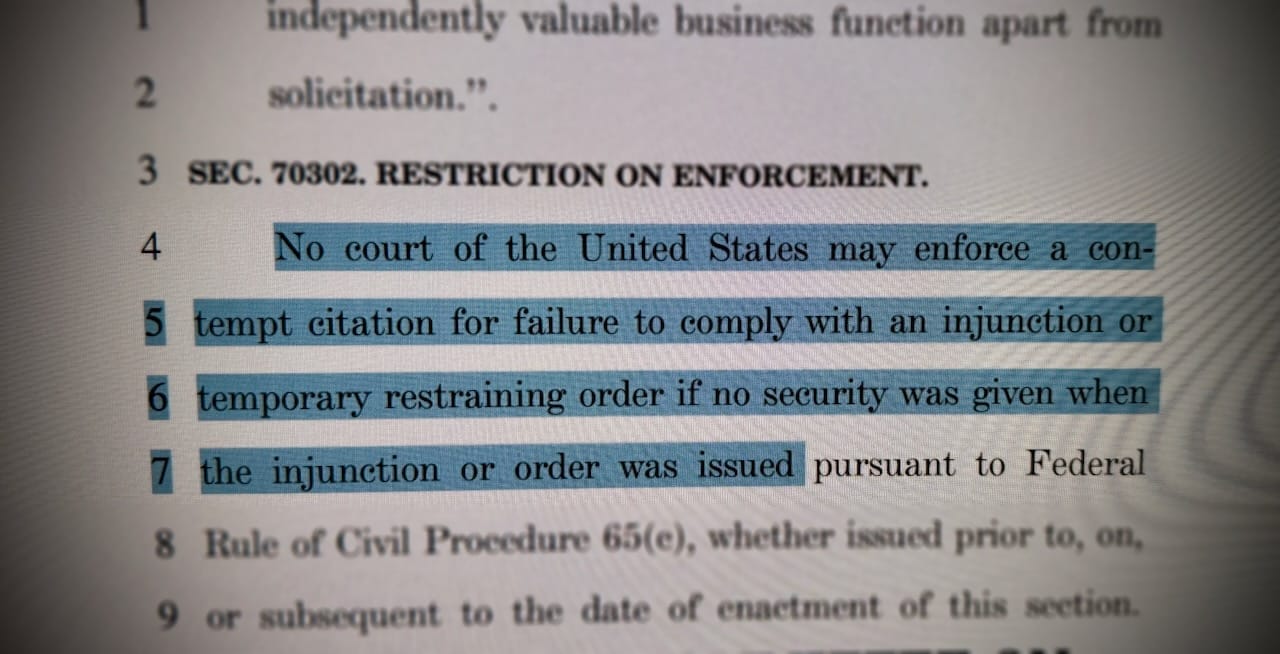

“No court of the United States may enforce a contempt citation for failure to comply with an injunction or temporary restraining order if no security was given when the injunction or order was issued.”

The provision applies retroactively and appears to tie enforcement to the posting of a bond—something public-interest plaintiffs rarely provide. Legal experts warn it could severely weaken federal courts’ ability to ensure compliance with lawful orders, especially in the most consequential cases.

Technically, the provision bars the use of appropriated funds to enforce contempt. But that subtlety doesn’t soften its effect: if courts can’t fund the enforcement of an order, their authority collapses in practice.

This isn’t just a budget constraint. It functionally disables one of the judiciary’s core enforcement tools—contempt—unless a financial bond was posted at the outset. And in civil rights and constitutional litigation, bonds are almost never required.

Consider the landmark case currently before Judge James Boasberg, who issued a nationwide injunction blocking deportations under the Alien Enemies Act. No bond was posted. Under this new clause, if the administration defies that order, the court would be powerless to respond.

Some legal scholars have suggested that courts might start attaching nominal $1 bonds to preserve enforcement. But such workarounds can’t retroactively fix older rulings—and the clause applies to past cases as well. Its practical result: defy a court order, and you may face no consequence.

The security requirement stems from Federal Rule 65(c)—a 1938 rule that lets courts require bonds to protect defendants from frivolous injunctions in private litigation. It was never intended to obstruct judicial oversight of government power.

The Power to Enforce

The U.S. Supreme Court has long held that courts must have the power to enforce compliance with their orders. In Young v. United States ex rel. Vuitton et Fils (1987), the Court affirmed that contempt is an inherent judicial power—vital to preserving the authority of rulings and the meaning of law itself.

Across American history, this power has upheld the public’s rights against entrenched resistance:

- During the Civil Rights era, contempt powers enforced desegregation orders—often against governors and officials who refused to comply.

- Environmental rulings halted illegal drilling or emissions—backed by the threat of contempt when ignored.

- Immigration courts protected asylum seekers and families by holding violators accountable.

Without the ability to enforce, a judge’s ruling becomes a polite suggestion. The rule of law becomes a coin toss.

Real-World Consequences

If this clause becomes law, its effects will be swift—and likely strategic:

- An oil company continues drilling in violation of a court injunction. No bond, no enforcement.

- A state official ignores a federal court’s block of an unconstitutional abortion ban. No repercussions.

- Federal agents violate a restraining order on detention practices. The judiciary is effectively paralyzed.

- A president overreaches during a declared emergency. A court rules against him—but can do nothing when ignored.

A Dangerous Convergence

This provision arrives just as concerns mount over the independence of judicial enforcement itself.

The U.S. Marshals Service, which carries out court orders—including contempt actions—is part of the Department of Justice. That means it answers to the president.

In 2024, several Democratic lawmakers introduced legislation to transfer the Marshals to the judicial branch, recognizing the risk of an executive branch that simply refuses to enforce court orders.

Senator Cory Booker, a co-sponsor of the legislation, warned: “Their dual accountability to the executive branch and the judicial branch paves the way toward a constitutional crisis.”

Under this new provision, even if courts act independently, they may lack the funds—or the means—to act at all. Judges would issue orders they know cannot be executed.

The Retroactive Threat

One of the most alarming features of the clause is that it applies retroactively—potentially nullifying the enforceability of existing court orders.

In Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, Inc. (1995), the Supreme Court ruled that Congress cannot retroactively overturn final judgments of Article III courts. Doing so violates the Constitution’s separation of powers.

This clause may not erase those judgments, but by withholding the means to enforce them, it renders them impotent—creating a shadow override of judicial authority.

The Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan watchdog, warns that the clause would “severely restrict federal courts’ authority to hold government officials in contempt, even in cases of blatant defiance.” Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has called it “a stealth attack on the judiciary embedded in a tax package.”

International Warnings

This tactic—eroding judicial enforcement—follows a pattern seen in other democracies.

In her 2025 Atlantic article, journalist Anne Applebaum documented how Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán systematically captured government institutions. She writes that Orbán “replaced civil servants with loyalists,” weaponized regulation against the free press, and politicized the courts—following “a very old, very familiar blueprint for autocratic takeover.”

Poland’s recent presidential election has cast uncertainty over its efforts to reverse years of democratic erosion. The victory of nationalist candidate Karol Nawrocki, backed by the Law and Justice party, suggests that rebuilding judicial independence may face renewed challenges.

What’s at Stake

The U.S. judiciary—despite a conservative majority—has repeatedly constrained executive overreach: from DACA to the travel ban to arbitrary deportations. The courts have been the final firewall.

This clause doesn’t challenge the legitimacy of court rulings. It challenges their enforceability. And in a democracy, that’s the difference between law and symbolism.

Already, opposition is mounting. In March 2025, Representative Laura Friedman (D-CA) and 20 other House Democrats condemned the clause, warning it “would significantly undermine the judiciary’s longstanding and constitutionally grounded authority to enforce contempt citations.” Senator Whitehouse and others have echoed those concerns.

The bill passed the House narrowly. It now moves to the Senate, where revisions are possible—but not guaranteed. Majority Leader John Thune has said he hopes to deliver the bill to Trump’s desk by July 4, giving critics little time to organize resistance.

Civil rights groups are preparing legal challenges. The Senate Judiciary Committee will take up the provision in the coming weeks. Citizens concerned about the balance of power should contact senators—particularly moderate Republicans like Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski, who may be swing votes.

Even if the courts eventually strike this clause down, it could do irreversible harm in the meantime: orders defied, enforcement stalled, and public confidence shredded.

And it all comes down to 63 words.

That’s just ~0.011% of the bill’s text—enough to upend 240 years of constitutional balance.

The Bottom Line

This is how democratic erosion happens—not with violence or spectacle, but with surgical edits. A quiet clause. A footnote of tyranny.

This isn’t just about a line in a budget. It’s about the rule of law itself. The question isn’t whether the courts will eventually strike it down. The question is what damage will be done before they do.

In that fragile space between a judge’s decision and its execution, justice either lives or dies.

This moment demands clarity. It demands courage. And it demands that we—citizens, jurists, institutions—act while we still can.

We cannot afford to find out what happens if we don’t.